How do you fancy building your own small wind turbine?

The UK has one of the world’s best wind resources, and exploiting it with small wind turbines is something that, in the right context, can be a very efficient source of power. Wind turbines, however, come with a fairly long list of handicaps when comparing them to other renewable technologies such as solar. One of these is planning and the sizeable ‘anti-wind’ lobby in the UK, something that, often due to ignorance, lumps small and big wind in together. Another is siting – due to small wind turbines operating at a much lower altitude than their larger cousins they are much more affected by obstacles such as trees and buildings, meaning that where they are placed has a huge effect on their efficiency. And finally, due to their having moving parts and being placed in very harsh conditions they are prone to break and need regular maintenance. However, even with all these handicaps, for those willing to undertake the adventure, small wind can prove highly rewarding.

Given the fluctuating nature of the UK’s renewable energy market and the handicaps of small wind mentioned above, many small wind manufacturers and installers struggle to stay afloat, leaving customers with turbines that they are unable to have serviced or repaired. This also means that many turbines on the market have very limited field testing and their long-term reliability is unproven which makes investing in them a bit of a gamble. Although there are good machines available on the market one increasingly attractive option, especially with the seeming demise of the feed-in-tariff, is to build your own.

The undisputed king of the self-built small wind turbine is the design by Hugh Piggott. The primary reason for this is that Hugh Piggott has been developing this design over more than three decades and using it to power the off-grid community where he lives on the west coast of Scotland. This means that the reliability and efficiency of the design can be demonstrated in a challenging real-world situation, not merely by some extrapolated calculations. The design has been adopted by many organisations around the world that want to take advantage of being able to build their own wind turbines as well as research groups wanting to test its efficiency and effectiveness as a means of rural electrification. The results are very encouraging, showing that a well-built Hugh Piggott machine performs comparably to commercial machines but with a much smaller capital outlay.

The Hugh Piggott Design

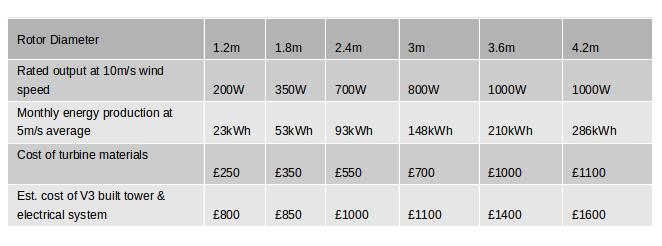

Hugh Piggott publishes his design in his Wind Turbine Recipe Book, which is a construction manual for the six different sizes of his turbine. The smallest has a diameter of 1.2m with a power rating of 200W, whilst the largest has a diameter of 4.2m and a power rating of 1kW. Exactly how much power any small wind turbine will produce is a difficult question to answer, but one that is often asked. The problem is that unlike solar radiation, the wind resource of a given location is difficult to predict. In addition, due to the nature of wind, a relatively small increase in average wind speed can result in a dramatic increase in generated power. Thus, the best, albeit slightly flippant answer when asked the question ‘What can that turbine power?’ is ‘What is your average wind speed?’. For example the 4.2m machine generates 67kWh a month at an average windspeed of 3 meters per second but will generate 286kWh if the average windspeed is 5m/s. But as mentioned above, this is a problem that all small wind suffers from – and the fact remains that given a good site it can be the cheapest form of renewable energy available.

The Hugh Piggott turbine has been designed with ease of manufacture in mind. It utilises relatively easily available materials and simple methods for its construction. This means that it can be built almost anywhere – from community workshops in Peru to a garage in the UK. This brings with it various benefits: firstly, it is often the cheapest option; secondly, local manufacture brings down the embodied energy of the final system; thirdly, it means that replacement parts can be easily manufactured when needed; and finally, it can be hugely empowering for the owner of the turbine, be that a community or individual, to have full control over their system and be able to deal with any eventualities themselves.

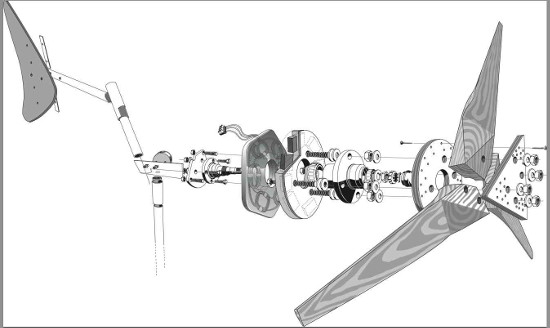

The turbine is made up of three sections – a metal mounting, an alternator made up of magnets and hand-wound copper coils cast in resin, and three hand-carved wooden blades. Everything is made from scratch except the bearing, which can either be a new trailer bearing or a salvaged bearing from a car or van. The entire turbine can be constructed entirely with hand tools, except for the welding. The alternator uses neodymium magnets, which are exceptionally strong and help to keep the overall size of the generator small. However, they are both expensive and have a relatively high embodied energy. The coils are hand-wound from easily available winding wire which means that when constructing the alternator you can optimise it to work with a battery bank of a given voltage or to be grid tied. Wooden blades mean that both manufacture and replacement is relatively easy. When maintained, wood is exceptionally durable and strong and when sourced responsibly is a fantastic sustainable resource. In addition to constructing the generator you also need a tower to put it on and an electrical system to connect it up to. It is important to include these costs when assessing the viability of a small wind system.

The typical use of a Piggott turbine is in an off-grid situation where it is used to charge a battery bank. It is particularly useful when there is already a solar PV system in place. Adding a wind turbine is often the best way to expand an existent off-grid system as you are able to do this without expanding the battery bank which is a significant cost in the system. By diversifying your generation capability to be able to generate at night and on cloudy days you are also able to minimise the risk of running out of power due to weather conditions, especially in winter.

Piggott turbines can also be grid-tied. Although effective on a technological level this is often financially imprudent in the UK at the moment due to feed-in-tariffs. Due to the self-built nature of the turbine it is unable to receive the feed-in-tariff and thus is unable to compete on a level playing field with other turbines. Nevertheless, it can still make sense to grid-tie a Hugh Piggott where your base-load electrical consumption is relatively high due to the bills savings that you will accrue. As the feed-in-tariff reduces and electricity prices increase, grid-tied Piggott turbines will become increasingly financially attractive.

Next Steps

For those interested in Hugh Piggott turbines there are a few things to consider. The first is planning. Although there is permitted development for small wind turbines, the Hugh Piggott turbines don’t comply as they are not MCS (the government’s renewable energy certification scheme) accredited and have a larger swept area than is permitted. However, the insistence on accreditation for planning is based largely on noise generation and there have been successful planning applications that use noise data for similar commercial machines to satisfy the local authorities. There have also been cases of successful retrospective planning being granted.

The second consideration is the site of the turbine. As mentioned above, the site has a huge impact on how well the turbine performs. The first thing is to check the general wind resource of your area. You can do this using online resources (http://www.rensmart.com/Weather/BERR). Then you need to check if you have a site that is not too obscured by objects such as buildings and trees that will block the wind.

If you are interested in getting a Hugh Piggott turbine you can simply order a manual – http://www.scoraigwind.com/axialplans/index.htm#BUY and build one. Or you can get an older version (but still a goodie) from Lowimpact here – https://www.lowimpact.org/build-wind-turbine/. Alternatively we at V3 Power run courses (http://v3power.co.uk/courses/) teaching people how to build Hugh Piggott wind turbines and can help in acquiring materials, giving advice or manufacturing parts or entire turbines/systems if needed. We have been building Piggott turbines for almost 10 years and are always keen to try to facilitate self-build wind turbine projects getting off the ground!

References/further reading:

Recent V3 Power Piggott installation – http://v3power.co.uk/install-at-nant-y-cwm-farm/

V3 Power – http://v3power.co.uk/

Hugh Piggot Blog – http://scoraigwind.co.uk/

V3’s Upcoming Courses: 3-4th October. Organiclea, Chingford, London. £225 / 10-11th October. V3 HQ, Nottingham. £225

To book a place and for more information visit: http://v3power.co.uk/public-courses/

- Get hands-on experience and learn transferable skills in welding, wood carving, and working with magnets & resin

- Learn how to build and install a Hugh Piggott wind turbine from scratch using basic materials

- Experienced tutors who have been running courses building Piggott turbines since 2007

- A practical fun course for all experience levels

On the course we collectively build a 1.8m diameter Hugh Piggott wind turbine. All the participants spend time working on each of the three main parts of the build (wood, metal, and electronics) rotating through the different bases on the first day. On the second day we then come together as a group to assemble the machine.

The views expressed in our blog are those of the author and not necessarily lowimpact.org's

12 Comments

-

1Dave Darby September 24th, 2015

Hi Jack – a couple of questions. Is it OK to grid-tie a turbine (or any kit) that isn’t MCS accredited? And you get paid for the electricity you export from a non-accredited turbine? How do you organise that?

-

2Morgan September 24th, 2015

Just the article I’ve been waiting for – thank you Jack

-

3Paddygoat September 24th, 2015

I’ve just bought the manual!

-

4V3 September 24th, 2015

As long as the grid tie inverter is “G83 approved” yes you can grid tie non mcs kit. Unless you are exporting MWh per year it is very unlikely you will be able to arrange to sell your excess electricity from a non mcs system. Contact your local DNO and ask to talk to someone in microgeneration.

-

5Dave Darby September 24th, 2015

Wouldn’t it be better to use batteries then – if you can’t sell your electricity from a non-MCS system, then you’re just giving free electricity to a large energy company?

-

6V3 September 24th, 2015

You can’t sell the electricity you generate but you can USE it which reduces what you use (and pay for) from the grid. If you use all the electricity you generate then you dont export any – like turning pumps and fridge/freezer compressors on or electrically heating water when its windy…

-

7Dave Darby September 24th, 2015

Yes I know – we’ve got a solar system here and we make sure we use the washing machine etc. during the daytime so that we can use what we generate. We also export to the grid and get paid for it (and get FiTs), because we have MCS kit – but you don’t, so I wondered why you’d grid-tie for a non-MCS machine rather than use batteries – or have I misunderstood?

-

8Andrew Rollinson September 29th, 2015

Dear Jack,

I’ve considered building a wind turbine before. Then I think about the battery vs. grid tie situation which has never seemed clear to me, and then I give up on the project. Can you please tell me:

1. How much does it cost to get the inverter and grid tie (G83) arranged and complete? Could you itemise everything? Who do you get to do the grid tie-in? Can it be a local sparky?

Also, aren’t inverters prone to break? To replace an inverter, wouldn’t it then mean having to get the specialist electricians out again?

I’m thinking here of a self-build turbine. I don’t go along with the motives for this MCS business.

2. The battery issue then puts me off, because don’t they need to be managed by being given a full charge periodically? Can you explain a bit about this with regard to a single wind turbine working through a battery?

Andrew

http://www.blushfulearth.co.uk

-

9Andrew Rollinson September 29th, 2015

What I meant to add was: The clearest plan I would have is to have a wind turbine and battery to power my fridge freezer, which is not in the house so I could set up an off-grid connection. This is my biggest annual energy consumer.

-

10Jack Howe October 5th, 2015

Hi Andrew – thanks for your questions.

1. An approved grid tie inverter costs between 50p – £1 per Watt capacity (i.e. a 1.5kW inverter is about £900).

On top of this you will need some over voltage protection system (for if/when the grid goes down or if the inverter has a fault). The cost of the controller varies quite a lot depending on what you are trying to do with the excess power. At the low end around £150 for a controler in the 1.5kW region. You will also need a dump load to put the turbines power into during such events – either a water or space heater is typical and costs around £100.

You need DC and AC isolation switches either side of the inverter and it’s also useful to have a switch to short out the 3 phase AC from the turbine to brake it for lowering/servicing etc. These switches each cost around £20 each.

You need a bridge rectifier to convert the 3 phase AC of the turbine into DC for feeding the inverter. The unit itself is around £15 but it wants a big heatsink too so budget another £10 for that.

You may want to put in an additional meter to keep an eye on what the turbine has generated. Most inverters have some form of logging but an ofgen approved meter will set you back about £20.

Finally you will want a MCB on your household circuit to wire into. A 16A one will cost around £10 but you may want/need to install it in a “garage unit” type box which is around £20.

Find a local sparky who has some experience of signing off solar systems as they will be familiar with inverters and isolation necessary for microgeneration. Depending on how much of your work they are happy to sign off on they should charge between £50 and £200.

It is worth budgeting for inverter replacement at around the 10 year mark. This shouldn’t require a sparky if you are replacing like for like.

2. Periodically giving lead acid batteries a good hard “equalisation” charge does indeed help prolong their life. Without it the cells can become imbalanced and the batteries degradation can be significantly accelerated. As you highlight this can be problematic with a renewable system as you have no control over the weather! Generally if you have a good enough wind regime to justify installing a wind turbine in the first place you will be getting enough days off good wind in a month to charge the batteries hard and keep them in good condition. With a battery charging system you will have some sort of charge controller unit which will monitor the state of charge of your batteries and dump excess energy to a heater once the battery is full. Many controllers can be programmed to periodically allow the batteries to be taken up to the equalisation charge level as soon as enough input power is available after a given date.

In terms of powering a fridge freezer you will need to obtain a large inverter to handle the startup surge of the fridge compressor. A typical fridge consumes around 100W when its compressor is running but you will need an inverter that can handle more like 1000W for the moment the compressor kicks in.

I hope this helps!

-

11Andrew Rollinson October 6th, 2015

Thanks Jack,

That’s very thorough and helpful.

I’ll need to do some sums to balance up the financial pros and cons. Even if payback is long, it’s an interesting project.

Andrew

-

12Robin Duval November 25th, 2015

Hello,

I’m Robin, I’ve recently taken over from Jack as V3 Power Co-ordinator and I just wanted to let you know about our Spring Hand Built Wind Turbine courses in London and Bristol where we’ll be building a 1.8m rotor diameter Piggott machine.

More info available on our website:

http://v3power.co.uk/16-17th-april-2016-hand-built-wind-turbine-course-at-organiclea-london/

http://v3power.co.uk/23rd-24th-april-2016-hand-built-wind-turbine-course-at-dee-workspace-bristol/

Hope to see you there!

Community vetoes for wind farms, but not for fracking? What’s that about?

Community vetoes for wind farms, but not for fracking? What’s that about?

How to get George Osborne to buy you shares in a wind turbine

How to get George Osborne to buy you shares in a wind turbine

Our experience of generating our own electricity for 25 years

Our experience of generating our own electricity for 25 years

Off-grid living: how big does your renewable energy generation system need to be?

Off-grid living: how big does your renewable energy generation system need to be?

How I came to write the third edition of ‘Wind & Solar Electricity’

How I came to write the third edition of ‘Wind & Solar Electricity’

Wind generators

Wind generators