The Yamagishi Association: successful, moneyless, leaderless network of communes in Japan and elsewhere

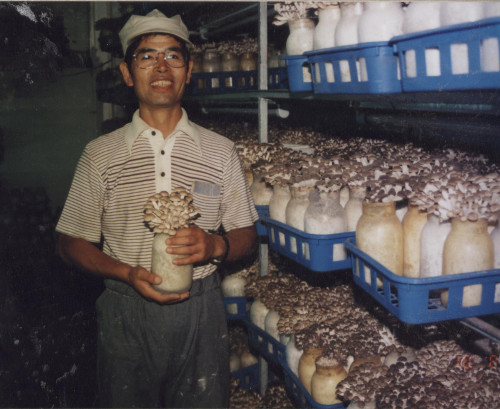

In the 1990s I visited the headquarters of the Yamagishi Association in Mie-ken in Japan. It’s a federation of intentional communities that is still going strong – but even then it comprised 3000 people in 30 villages all over Japan (4000 people in 40 villages in 2001, more like 5000 people in 50 villages now), with other villages in Australia, the US, Germany, Switzerland, Thailand and Brazil.

[NB: the Yamagishi Association had some bad press in the 1990s, when they were sued by several ex-members, claiming that they had been ‘brainwashed’ into giving away their savings. However, the people live in the Yamagishi communes without money, and are asked if they’d like to donate to the cause when they join. No-one checks new members’ bank accounts, so it’s possible to donate only a percentage of what you have – or none at all. Most people are happy to donate to the cause. In fact, if you join a movement that wants to promote a society without material possessions, then giving up your possessions seems the apt thing to do. The woman who brought the highest-profile case was refused membership twice on the grounds that she did not subscribe to the ideals of the movement, and it seems they were right. Courts rejected brainwashing claims, as well as claims that there are ‘leaders’ who live in luxury, but in some cases ordered the return of some money, because their methods run counter to Japanese social customs. I stayed in Yamagishi villages for a total of two months, and I am as sure as I can be that there are no ‘leaders’ or even bosses.]

In the 1950s, Mr Yamagishi was a chicken farmer who devised the perfect system for chickens – he stipulated the size of pens, the number of birds kept together, number of cockerels in with the hens, depth of litter, type and amount of food and size of brood boxes – everything. His system doubled egg yield, and brought chicken farmers flocking (I know, sorry) from all over Japan. He then got a bit more ambitious and devised a similar system for humans, based on communication – what humans like to do most, according to Mr Yamagishi.

Since my visit, I read Michael Albert’s Parecon, and a lot of the ideas are similar – the lack of money and bosses, the intricate decision-making processes based on several different ‘kensan’ meetings. It’s a theme I’ll explore more in later articles.

Here are my notes from my visit.

————————————————————————————————————————

Named after their founder, I’d had information about the Japanese Yamagishi villages sent to me in England, so I knew that they were a pretty impressive operation: three thousand members living in thirty communities, supplying fifty different food products to a million customers.

Toyosato is the headquarters of the Yamagishi Federation, located near Tsu-shi (city) in Mie-ken, another 400 km south from Tokyo. As I said goodbye to my final lift, I could see the large white buildings of the complex on top of a hill, and I made my way towards it. It was a veritable hive of activity; lots of people going about their business in a general atmosphere of industry and friendliness. I made my way to reception and Akiko was called for. Akiko was in charge of overseas visitors, and had the best command of English of any Japanese person I’d met till then. She showed me to my room and made me feel very welcome. I was to relax for today and she’d show me around tomorrow.

During the next day’s tour I remember thinking that the cows, pigs and adult humans didn’t have much leg room, but that’s Japan. The chickens and kids though, appeared to have plenty of space, which was nice. As the tour progressed, I realized that most of my questions were being parried in the same way: basic practicalities were being explained, but I was continually being told that the deeper meaning behind things could not be explained sufficiently without my having done ‘tokkoh’. It appeared that this mysterious tokkoh was a week-long intensive course which gave one an insight into the even more mysterious kensan, which forms the basis of the Yamagishi way of life. I was encouraged to do tokkoh, as no English person had done it before, and Akiko would translate for me. I was reassured that there was nothing ‘cultish’ about either the Yamagishi villages generally, or tokkoh specifically, although I didn’t really care, I wanted to do it anyway; I wanted to understand what made this place tick – the second largest organization with a common purse I’d come across, after the kibbutz, and possibly the most efficient. There was a problem though: it was too expensive for me – around two hundred pounds.

While I was thinking about this I went off to see another jikkenchi near Osaka. A rather specialized community this one, it received, processed and re-distributed all the human and animal excrement from all the local Yamagishi communities. It is stored in huge piles, mixed with bark and various other bits of vegetation and turned regularly. It is then sent back to the communities as prime compost to be used on the land, and the surplus is bagged and sold. A compost community.

When I got back to Toyosato I was made an offer. Work here for twenty days in exchange for tokkoh, with Akiko to translate. Miachi-san, one of the elected leaders of the movement, would then answer any questions I might have, and I would be in a better position to understand his answers. I accepted.

There are two curious things about meal times here. First, there are only two a day, at eleven and six, but they’re both huge enough to keep you going. The other is that it seems to be taboo to waste food. Every morsel is eaten, down to the last grain of rice. A good thing too, and anyway, it’s not difficult as the food is utterly delicious, as is most food I encountered in Japan, apart from pseudo-Western food, which is awful. Everyone helps with the washing-up. The Japanese are so good at this sort of thing; no-one seems to want to do too little. They use the waste from the rice crop in little net bags, instead of detergent, but I didn’t find out exactly how it works, as when Akiko wasn’t around, everything was reduced to mime. They were very patient, and tried to teach me a little Japanese; I began to see the necessity of learning.

I started working with the chickens, which was apt, as this is how the Yamagishi system started – as a chicken farm. Mioso Yamagishi (1901- 61), who was later to have many interesting ideas about the organization of society, first applied himself to the organization of the chicken run. He wanted to create the ideal environment for chickens and thus produce the highest possible number of high-quality eggs. Careful observations told him that they thrived best in groups of twenty-five, with five cockerels (so that it’s not just the eggs that get laid). They needed to be able to walk around and scratch in deep litter, and be relatively open to the elements, but safe from predators, and able to shelter from the rain. He came to precise figures for the amount and types of feed that they should be given, and the exact dimensions of the sheds and nesting boxes. It works too; healthy, plump (almost swaggering) chickens, and tons of eggs. Having developed the perfect living environment for chickens, he turned his attention to humans, and in 1956 he organized the first tokkoh, attended by 180 people. Many more tokkohs followed, mine being the 1,431st, with an average of over 200 attending each one. In 1958, 400 tokkoh graduates got together to form a community. They sold all their possessions to purchase land and start the first jikkenchi at Kasugayama, and the federation has grown from there.

After 3 days working with the chickens, I could hardly stand up straight, as I’m too tall to comfortably collect the eggs from the nest-boxes, so I transferred to the pigs. During this time I met a German couple who told me that there were two jikkenchis in Germany, one of which they were members of, and that they were here to study Japanese methods. They were enthusiastic about kensan, but were not impressed by the uniformity that they found here, and said that German Yamagishi communities would allow much more freedom of expression for members. As an example, they mentioned the fact that there were huge bathrooms here, with showers and large communal baths, (men and women bathing separately). At home however, they like nothing better than to share a bath together, in private, with a bottle of wine, and so that’s exactly what they do. The uniform behaviour here is typical of Japan and not of the Yamagishi system specifically. There are jikkenchis in other countries too (Korea, Thailand, Switzerland and Brazil), all possessing the flavour of the host country.

From the pigs I graduated to vegetable picking, which was very pleasant – strolling along, throwing ripe sweetcorn over my shoulder into a sack on my back, and watching terrapins dive from the banks of the ditch at the side of the field into the water as I approached. That is, until the heavens opened, and we all went for an indoor picnic, and I was forced by peer pressure into joining in with an awful Japanese song to the tune of ‘Beautiful Sunday’. The villagers have an incredible enthusiasm for their kensan way of life, but this was taking it a bit far, I think. Talking of enthusiasm, I’ve never seen such hard-working teenagers. If they’re not studying they’re working in the fields or in the polytunnels, picking or packing vegetables; surreal. I couldn’t work out if it was a Yamagishi or a Japanese idiosyncrasy. There was a lot I couldn’t work out actually, but I was constantly and frustratingly being told that I wouldn’t really begin to undertand anything until after I’d taken tokkoh, and I was becoming impatient.

I passed my spare time talking with a group of Swiss young people who were there to attend kensan school, which continues where tokkoh ends, and goes deeper into the art of kensan, the thing they do most joyfully, and which was still a mystery to me. Most were intending to join one of the two villages in Switzerland. I also swam in the large outdoor pool, and sometimes wandered over to have a look at the activities in the ‘Children’s Paradise’, a holiday centre for several hundred (non-Yamagishi) children at a time, from all over the country. On successive evenings I witnessed a tug-of-war contest and a musical play where a super-hero called ‘Captain Vegetable’ (or something similar) and his trusty band of vitamins helped to destroy diseases and the forces of evil. Both went down a storm. Income from these children’s camps only manage to cover costs, but are seen as invaluable in spreading Yamagishi ideas amongst children, not to mention parents.

So just what are these ideas? Well, I was about to find out, as the time had come to do tokkoh.

I went with about 240 other curious people from all around Japan to a special jikkenchi located near Kyoto, on the top of a mountain, far away from everyday distractions; but just to make sure, we had to give up all our possessions on entering, except changes of clothes. No wristwatches were allowed, no newspapers, books, radios, TVs, or anything to remind us of the outside world. We were split into two groups of 120 for the tokkoh sessions, and we all came together to eat, and to perform the classic early-morning exercises, outdoors, before the day’s sessions began. In a large room containing nothing but tatami mats, we all sat in a large circle, three deep, with two Yamagishi members in the middle to co-ordinate the discussions. These discussions centred around certain questions which were posed by the co-ordinators, who then let us get on with it. I have to say here that before tokkoh started, the co-ordinators elicited promises from us not to divulge exactly what these questions were, and so for me to include them in this book would be a breach of trust to say the least. What I can say though, is that they were designed to help people to examine themselves, then society, and then to hopefully try and change both. The course’s aim was to try and increase people’s happiness by addressing questions of anger, ownership, and freedom to do what one wants. The questions themselves were very simple – initially there was a feeling that they were indeed too simple, and that the course was a bit of a sham. However, the secret was in the amount of time that we had to spend on a question that we wouldn’t usually bother to think about at all. For example, we managed to collectively ponder over the initial five-word question for two days, bolstered with plenty of tears and hugs. Sessions would go on until the general feeling was that we wanted to finish, as no-one knew what time it was anyway. There was no teaching on the course; participants were encouraged to think for themselves and come up with their own conclusions, sometimes involving a lot of honesty, and emotion. To say that all this was interesting is quite an understatement, and I feel privileged to have been allowed to obtain such an insight into the Japanese psyche.

Tokkoh finished with a visit to villagers in their rooms, then a big party and a meal. By this point I thought I had a basic idea of what kensan was: literally, I think it means something like ‘reflection’, but as a tokkoh graduate, I could have taken kensan school for two weeks to find out more. Each month, about 25 tokkoh graduates and their families join the Yamagishi Federation, and spend some time at Toyosato learning more about kensan, before going off to join an established jikkenchi elsewhere. New recruits give all their assets to the Federation, which, together with income from sales of produce, enables them to buy farms and start new communities. Numbers of both members and villages are rising rapidly. The spreading of the kensan idea is seen as the most important goal though, rather than merely attracting new members to the communities. Kensan is practised by tokkoh graduates in the wider community too, rather like Alcoholics Anonymous meetings. It’s true though, that I couldn’t really have begun to understand Yamagishi philosophy without having done tokkoh. I was very drawn to their ideas, although it was frustrating because of the language barrier, and I couldn’t help feeling that I was missing something vital. I could see the value of kensan in trying to arrive at the truth. In a kensan meeting, anyone can discuss anything that is important to them at the time, with the aim of engendering a mutual understanding between participants. After all, how much bad feeling and hatred, and how many wars are due to mistrust and fear based on misunderstanding? Differences of opinion can be aired in kensan but without anger. Here is an important lesson for communities in the West: how to air feelings openly and to avoid misunderstandings. Since then I have read that tokkoh is actually an abbreviation of tok-kotai, which means ‘special attack corps’, better known as the kamikaze corps in the West! In this case though, the suicide is metaphorical; the aim is to ‘die to self’, or in other words to put aside ones own selfish interests in favour of the interest of the group, and ultimately society as a whole.

I read some of Mr Yamagishi’s book, the English version of which was then only half completed. He was certainly very ambitious, and ultimately wanted to change the world. If they keep expanding at this rate, it can’t be far off.

As I’d finished tokkoh now, Miachi-san agreed to answer a few questions for me.

Of the 3000-plus members across Japan, 600 of them were at Toyosato, either as permanent members there, or preparing to move to a village elsewhere. Members attend kensan meetings for their particular living area, and for their work area. An example of how this works: it became clear from the meetings of several living groups that many people wanted a swimming pool. The proposal was discussed in all kensan meetings and it was indeed decided to build a pool. The decision was passed to the kensan meetings of the Housing and Environment department, who decided where to put it, and arranged for it to be built in consultation with the Accounts department, who paid contractors to do the job.

After tokkoh and kensan school, potential members have a six-month trial period, after which time they give their assets to the community if they decide to stay. Membership can be refused though if, after kensan, members decide that a prospective member doesn’t share the groups values, i.e. wants to join for selfish reasons and not for the benefit of the immediate and wider communities. If accepted, the new member can choose what kind of work he or she wants to do, and there will be kensan to find out if this kind of work is needed. If a new member has a profession, he or she can practise that, either for the village or outside, and if not, there are plenty of community jobs to do – for example: agriculture, orchards, pudding and ice-cream factory, food processing, computers, compost, tea, timber, laundry, construction, architecture, health, education, cooking, cleaning, nursery, administration, driving, sales, finance, safety inspectors, mechanics and maintenance. Members work 8-hour days, and there are no set days off. These are taken when required, which in my experience wasn’t all that often. People seemed to prefer working to leisure. Again, this probably has more to do with Japan than Yamagishi. Toyosato also employs 200 outsiders. Money is available for members to purchase things from outside, and the system is the same as for days off. There is no limit, but members are trusted not to overspend. And they don’t.

From Toyosato I was headed for the bright lights of Tokyo to look for a job to fund the rest of my trip, but this time I didn’t have to hitch, as I was offered a lift in a Yamagishi truck – one of many in their nationwide distribution network.

I was to return however, one year later, which is where I’ll pick up the story again now. It was summer again, and I was waiting for a lift that would take me the final few kilometres to Toyosato, when a police car pulled up alongside me, and asked me to get in. I assumed that I’d been hitching in a place I shouldn’t and I was in trouble. But no, they asked me where I was going and yes, you’ve guessed it, they gave me a lift. Only in Japan.

When I arrived, preparations were in full swing for the annual Yamagishi free festival, from which they recruit many of their tokkoh students. I joined a group who were hammering nails and painting signs for a stall which was to be an international coffee shop. I worked with Syrians, Vietnamese, Chinese, Indians, Germans, Swiss, Americans, Canadians and a Brazilian, who was from a jikkenchi in Brazil and he told me that yes, it did have a definite Brazilian flavour: more spontaneity and less conformity than in Japan.

100,000 people turned up for the festival. Everyone ate as much as they liked, all day, and the food, which was all produced in the Yamagishi villages, was free. Non-members who have taken tokkoh turn out in force too, to donate their carpentry, electrical and cooking skills in setting up the event, and also to offer services as part of the festival itself; for example, a local barber arrived to cut people’s hair for free. I met some people again who were in my tokkoh group, and there was immediately a special rapport between us even though we knew so little about each other’s lives.

After the festival there was an international meeting of foreigners recruited through the international café, to try and explain Yamagishi ideas a little more, and to get some feedback. Many questions were asked about environmental policies, an area where it soon became obvious that there was more awareness in the West than in Japan. A spokesperson explained that they use no artificial fertilizers, very few agricultural chemicals, and are trying to phase them out completely. It was also explained that although the animal pens appeared small to Western eyes, they were bigger than average in Japan, where the idea of cruelty to animals is not well developed (in Tokyo I had been taken by a friend to a restaurant where the fish had a reputation for freshness. It was certainly deserved; flesh is sliced from the fish while it is still alive, and it is served up next to your dish with its backbone and brain still intact and its mouth opening and closing. Or you could choose a soup of live baby fish and feel them wriggling around in your belly). Policies on the keeping of animals is something that can change with kensan.

Another feeling that most foreigners shared was that they would rather live in a place that looked like a farm than one that looked like a factory, and I have to admit that Toyosato seemed to me to be a little too close to the latter, although according to one author, aesthetics is another area where Japanese and Western thought diverges. Japanese people can appreciate beauty in a particular object and ignore its surroundings, such as a solitary cherry tree surrounded by acres of concrete in a city, or in the case of Toyosato, a line of bonsai and a traditional rock garden in the middle of modern, industrial-looking animal pens, offices, warehouses and accommodation blocks. I noticed too, that around Japan, people were not in the least fazed, like I was, by tannoy systems in parks, or fizzy drink vending machines on mountain trails. Uglification is only caused by demand for it. Residents of idyllic holiday locations are eager to cover their villages and countryside with asphalt and concrete if it means making more money, and in the West we talk a good game when it comes to the environment, but that’s about all.

I was to find out more about Yamagishi-ism in Australia (see Cairns Yamagishi Village), but a final word about Yamagishi communities for now: by my second visit, I had realised that almost all of my initial criticisms of their way of life were in fact criticisms of the bewildering social system of Japan, a conclusion I’d come to after living for ten months in Tokyo’s densely-populated mega-conurbation of over thirty million.

The views expressed in our blog are those of the author and not necessarily lowimpact.org's

9 Comments

-

1screenbeetle November 17th, 2015

Fascinating article Dave. Some nice reminders of my own years in Japan – especially the often brutal tannoy systems.

Japan often gets a really bad press related to issues like whaling and over fishing. While it has its major flaws – like any country – I reckon there is an awful lot to be learned from it – culturally, philosophically and, of course, technologically.

For starters there is a lovely depth of honesty in most of the Japanese people I met. An example being the Fuji Solstice festival we went to where 10,000 people lined up neatly to pay entry when they could have just walked in for free from any part of the fenceless site. The only people that seemed tempted not to pay were me and my fellow westerners.

-

2Paul Jennings November 17th, 2015

Thanks for that, Dave, much appreciated mate.

-

3Dave Darby November 17th, 2015

I thought you’d like it, being an Albert fan. The language barrier was a problem (although I was chatting quite nicely by my second visit), but it certainly does look a lot like Parecon – and it’s definitely something that can be pointed at to show that ‘something like’ Parecon could work in the real world.

-

4Gray May 20th, 2018

Wonderful article! It sounds like you had an amazing experience. Out of curiosity, do you know if Yamagishi communities have access to the internet and similar resources, or are they more similar to Amish communities in America that tend to reject a lot of non-necessary technology?

-

5Dave Darby May 21st, 2018

Hi Gray – no, they’re quite high-tech. They have IT-based businesses too. Here’s their website – https://www.yamagishi.or.jp/ (in Japanese).

-

6Kylie Chang October 14th, 2019

Hi Dave! I am working on a project about the Yamagishi Utopia. Do you know if you can reply to me about the key details? I’m on a time crunch, and I don’t really understand parts of your article. Thank you for the generosity of enlightening me about the Yamagishi!

-

7Dave Darby October 15th, 2019

Kylie – which parts need clarifying? I’ll have a go, but it was a long time ago.

-

8Kylie Chang October 19th, 2019

Dave- Thank you so much for responding! I was in need of clarifying about where the community is, and if they had any failures or special achievements.

-

9Melissa E. Brown September 28th, 2022

I’d love to visit for a few months. Sounds familiar and productive. Plus, they’re usually clean, organized and cohesive.

How to answer the question: ‘if you don’t like this system, what do you want to replace it with?’ – aka a review of The Democracy Project by David Graeber

How to answer the question: ‘if you don’t like this system, what do you want to replace it with?’ – aka a review of The Democracy Project by David Graeber

More details of the ujamaa collective village system in Tanzania (from first-hand experience)

More details of the ujamaa collective village system in Tanzania (from first-hand experience)

How Julius Nyerere’s Ujamaa idea could form the basis of a new global political system

How Julius Nyerere’s Ujamaa idea could form the basis of a new global political system

What might poultry farms and human society look like if chickens and humans weren’t treated as machines to maximise profit?

What might poultry farms and human society look like if chickens and humans weren’t treated as machines to maximise profit?

Diggers and Dreamers Communities Directory is back with a 25th anniversary edition

Diggers and Dreamers Communities Directory is back with a 25th anniversary edition

Commoning

Commoning

Intentional communities

Intentional communities

Philosophy

Philosophy

System change

System change