“Community land trusts lock in value for the benefit of their communities for the long term.” – Anthony Collins Solicitors

What are community land trusts?

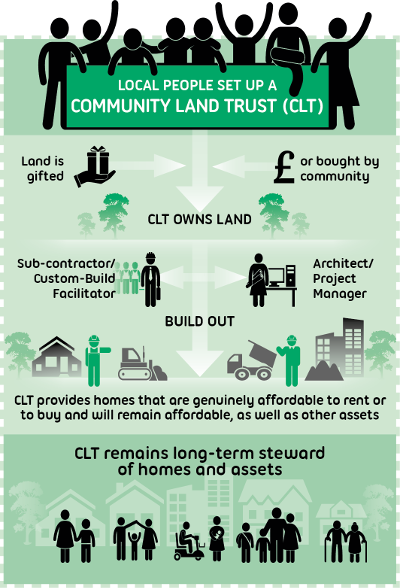

Community land trusts (CLTs) are local, not-for-profit organisations that steward land and property democratically for their local community. They’re set up and run by volunteers to own and manage housing and other local assets (like pubs, green spaces, community centres, shops or workplaces) for the benefit of the community. Those benefits include affordable housing and essential services, and they are legally protected in perpetuity.

The CLT retains the freehold on the land, and rents or sells buildings to residents or businesses at affordable rates. If properties are sold, it is via long-term, renewable leases, so that residents can obtain mortgages and pass on the property to family members. The CLT retains the right to buy back the property at a fair price, that will recompense the leaseholders for the mortgage payments and improvements they’ve made. This way, properties are taken off the market and kept affordable.

Land is obtained by a CLT in a variety of ways. It’s sometimes bought, with the help of grants or donations from government, charities or other bodies or individuals, or via community share issues; or the land might be donated (by an individual, local authority or by a developer that is required to set aside land for community benefit as part of a private development) or provided cheaply – for example, by a local authority. Sometimes a CLT can purchase land (often on the edge of settlements) relatively cheaply, because it isn’t in the development zone, but then obtain planning permission that would not be granted to any other organisation (the investments will be recouped quickly from rents and leases from properties that would not otherwise have been built). The CLT then works with builders, developers, housing associations or self-builders to build homes and/or develop other community assets.

The land / properties that a local CLT owns do not have to be contiguous – i.e. it can own scattered parcels of land throughout the locality. They can be urban or rural, and don’t have to be new-build. Often a CLT will buy empty properties and refurbish them.

CLTs differ from housing co-ops or cohousing projects, which are owned and run by and for their members, whereas membership of a CLT is open to everyone in the local community.

There are certain things that CLTs are legally obliged to do:

- be set up to benefit a defined community

- return any surplus income to that community

- offer membership to local people

- allow members to control the CLT (usually by electing a board)

Introduction to CLTs in the UK, published in 2016, when it said that there are 175 CLTs in the UK. At the time of writing, there are 225 and rising.

History

The thread of inspiration for CLTs is fascinating. The roots lie in the co-operative movement in the UK in the 19th century. Their ideas influenced Ebenezer Howard and his garden cities in the early 20th century, which were intended to be ‘co-operative land societies’ with any surplus ploughed back into civil facilities and affordable housing, although it didn’t turn out that way. This influenced the Gandhian Bhoodan-Gramdan movement in India in the 1950s, that gifted over 1 million acres to be held in trust for landless peasants. This in turn inspired Martin Luther King, and the first official CLTs emerged from the civil rights movement – like New Communities Inc., formed in 1969 in rural Georgia for African American ex-sharecroppers. The first urban CLT was set up in Cincinnati, Ohio in 1981, and CLTs started to take off in the US in the 1990s.

Inspired by the success of CLTs in the States, pilot projects were run in the UK at the beginning of the 21st century. The National CLT Network was launched in 2010 to promote and support CLTs across the country. Now there are hundreds of CLTs in both the US and UK, and movements have begun in other countries too – notably Australia, Belgium, France and Italy, as well as individual projects in Africa and Latin America.

What are the benefits of community land trusts?

CLTs can help stem the tide of insanely spiralling land and property prices, by keeping housing affordable. So many young people find it impossible to buy a home, can’t afford private rents, and therefore find it difficult to stay in live in communities in which they grew up. Meanwhile more and more houses are being used for speculation and second/holiday homes. Added to this, population is rising faster than homes are being built, and a lot of people are becoming homeless or living in very poor conditions.

CLT rents and sale prices are based on local median income levels, rather than what the market will bear, which is driven by property speculation. So for example, the average price of a 2-bedroom flat in Tower Hamlets in 2017 was £550k, but the price from East London CLT was £181k – based on annual housing costs being no more than one-third of median income in the area (i.e. one-third of £31k). If we want key workers such as nurses, teachers and bus drivers to be able to afford to live in the communities they serve (especially London), then projects like this are essential.

Roots of the CLT: chapter 1 of a wonderful 4-chapter history of CLTs in the US; and here are chapters 2, 3 and 4.

They’re particularly beneficial for neighbourhoods with lots of boarded up shops, closed pubs, disappearing banks and post offices etc. They can make communities better places to live and work, by giving the community more control, and they succeed where other regeneration initiatives fail.

CLTs tend to work with small, local building companies rather than huge developers (so that money stays within the community), and they take land off the market forever, so that it is no longer used as a speculative tool for private profit, but for homes and strong, vibrant communities. We think that these are good things.

They can also be seen as a tool for taking back and expanding the ancient ‘commons’ – a word used to describe vast areas of land that were held as a common asset (for example for grazing livestock or collecting firewood or wild food) before they were largely forcibly removed from communities during the ‘enclosures’.

What can I do?

Join the CLT Network and support them in their campaigns – for example to exempt CLTs from right-to-buy legislation (which would make it impossible for CLTs to keep housing affordable in perpetuity). The CLT Network has a listing of UK CLTs on its site, as well as some that have open days and events.

In Scotland, there are lots of community land projects that operate in exactly the same way, but aren’t officially called CLTs. The umbrella organisation for Scotland is Community Land Scotland, who have listings for Scotland too.

How London CLT provided affordable housing as part of the redevelopment of a derelict hospital in Bow, East London.

Starting a CLT

This is a big task of course, but here’s what you do: first identify what you want to achieve in your community – maybe it’s affordable housing, turning waste land into a park or city farm, saving a local pub or shop, or providing office or workshop space for local businesses, or a combination of several of these aims. You need to talk to as many people as possible to make sure that it’s what your community really wants. You could do this by holding a public meeting, where you could canvas opinions and ask for volunteers. Then get together a group of people to form a steering group (which will possibly turn into the board of the CLT once it’s established).

Then, really, just contact the CLT Network or Community Land Scotland and ask for guidance from there. There’s funding that you can access to get started – to get technical advice, produce a feasibility study and business plan, work out the best legal structure and incorporate. ‘Community land trust’ is not itself a legal form, which could be one of various types of not-for-profit – the most popular of which are community benefit company, community interest company (CIC) and company limited by guarantee limited charity. See the CLT Network for advice.

NB: a CLT can’t be a co-operative society because it’s set up for the benefit of its community, whereas a co-op is set up for the benefit of its members.

Running a CLT

There are further sources of funding after you’ve set up – to investigate sites, to do further planning etc. But the CLT Network can guide you at every point in your development, including sources of funding.

You need to work constantly to build support and membership locally – after all, CLTs exist to provide benefit for the community as a whole, not just for part of it. This will be helpful when it comes to planning applications, for example. Also, stay in close contact with your local authority and with a neighbourhood planning group if there is one (you may be able to help them achieve their aims).

Good governance is all-important. This is best achieved by having a board consisting of people with a wide range of skills, including finance, planning and law, as well as a knowledge of business and the local area. Membership of the CLT Network gives access to handbooks, health checks and specific advice on management and governance of a CLT, plus customer care etc.

See here for many more resources on setting up and running a CLT.

Thanks to Beth Boorman of the National Community Land Trust Network for information.

The specialist(s) below will respond to queries on this topic. Please comment in the box at the bottom of the page.

Peter Burke is a director of A Fairer Society. According to Peter, “My purpose is sustainable development projects. How to create a proposition and a model that investors will trust and invest in. Especially for community-led / asset-backed projects, with my main focus on housing. My passion is designing a feasible plan with social, financial &/or environmental purpose.”

Peter Burke is a director of A Fairer Society. According to Peter, “My purpose is sustainable development projects. How to create a proposition and a model that investors will trust and invest in. Especially for community-led / asset-backed projects, with my main focus on housing. My passion is designing a feasible plan with social, financial &/or environmental purpose.”

The views expressed here are those of the author and not necessarily lowimpact.org's

Low-impact building

Low-impact building

Building societies

Building societies

Co-operatives

Co-operatives

Cohousing

Cohousing

Commoning

Commoning

Commons economy

Commons economy

Community

Community

Housing co-operatives

Housing co-operatives

Housing commons

Housing commons

Planning permission

Planning permission

Low-impact retrofitting

Low-impact retrofitting