“Large-scale problems do not require large-scale solutions; they require small-scale solutions within a large-scale framework.” – David Fleming

What is ‘small is beautiful’?

Small is beautiful’ is a philosophy that favours small shops and restaurants rather than enormous supermarkets and chains; small farms and smallholdings rather than huge monoculture agribusiness; small-scale manufacturing rather than corporations; local credit unions rather than multinational banks, and so on.

The reasoning is that the scale of large businesses subverts democracy, damages nature, provides unfulfilling work and blandness instead of uniqueness. ‘Small is Beautiful’ was the title of a 1973 book by E. F. Schumacher, who went on to found the Intermediate Technology Development Group (now Practical Action), helping to set up small enterprises in less-developed countries.

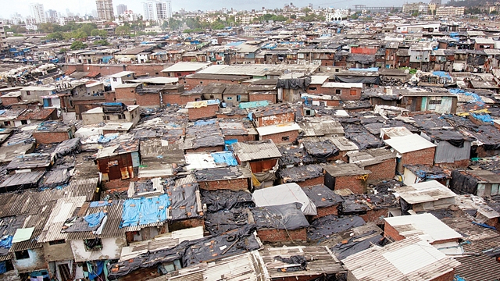

The introduction of plantations and factories, producing for multinational corporations, into those countries destroys small farms and businesses and forces people into grindingly boring, unskilled and exhausting work for very little money, and the profits are exported out of the country. The scale means that they are capital-intensive rather than labour-intensive, which means that small businesses can’t compete when it comes to the capital investment required, and that millions of small farmers are forced off their land and into urban slums and unemployment.

Distributism

‘Distributism’ was an early 20th-century movement urging that wealth and power be spread thinly through society, not concentrated in corporations or the state. In capitalism, the ‘means of production’ (land, tools, factories, offices, machinery etc.) are mainly owned by large businesses, and under socialism, the means of production are mainly (or completely) owned by the state. In a distributist society, everyone owns the means of production, either individually, or in partnership / co-operatively with other people.

So small farmers own their land, tractors etc; self-employed plumbers own their tools; shopkeepers own their shops; IT folks own their computers; small manufacturers own their machinery; and everyone owns their own home – either individually or as part of a co-op. It’s not about redistributing wealth directly, it is about redistributing ownership of the means of production, so that people can generate their own wealth.

Distributism actually has conservative (and Catholic) roots – radicals came along later. In 1891, Pope Leo XIII issued a statement, the Rerum Novarum, that criticised both communism and unrestricted capitalism, and stressed the need to spread the ownership of property thinly. In the first half of the 20th century, G. K. Chesterton and Hilaire Belloc (both Catholic, but influenced by the growing co-operative movement in Britain) turned it into a political movement. Dorothy Day and the Catholic Worker Movement came on board in the middle of the century, along with socialists who were unimpressed with developments in Stalin’s Soviet Union. Opponents of distributism have never been able to hang a left or right label on it, because it isn’t either.

Neither left nor right

The ‘smallist’ message to the left is that collective ownership of the means of production works well on the small, local scale, where people know each other – housing co-ops, worker co-ops, community energy schemes, land co-ops etc. – but not on the large-scale because trust is lost, it becomes overly bureaucratic, alliances are made with big business, and it can end up concentrating power in the wrong hands.

The message to the right is the same – private ownership of the means of production works well on the small, local scale – small businesses and shops, smallholdings, family firms, self-employment – but not on the large scale because it concentrates power in the wrong hands.

Politically, it’s about the principle of subsidiarity – that decisions should be made at the lowest, most local level that can deal with them. That’s it – it’s not about destroying competition or the market. The opposite of competition is not co-operation or collectivism, it’s monopoly.

The role of the state

‘Giantism’ doesn’t happen without state intervention. As a company grows, internal bureaucracy and communication channels become further removed from the market, and they become inefficient and slow to react compared to small companies. Plus their distribution networks get bigger, with higher transport costs. The state helps large institutions to externalise their internal inefficiencies and costs, so that the taxpayer ends up paying for the things that are called ‘economies of scale’.

The taxpayer pays for the road, rail, airports and communications to allow big business to spread; the military bill to help them force their way into other countries; the environmental costs, whether they can be cleaned up or not; education for their workers; health care and sickness pay when their employees become sick; their research and development; and even to bail them out if they fail. Plus compliance with growing state legislation is more burdensome for smaller organisations than it is for large ones.

The same tendency towards giant organisations happens in nationalised industries in more socialist-leaning countries, and even in the co-operative sector. The Co-op Bank would not have stumbled and been swallowed by a hedge fund if it had remained a federation of small co-op banks in every town, rather than merging into one giant institution. ‘Giantism’ produces the same problems whether corporate, state or co-operative.

Mutual credit

Mutual credit is a growing movement of local, trusted networks for small businesses to trade with each other without money. Everyone gets an account; if someone buys from you, your account goes up, and if you buy from someone else, your account goes down. There are limits to how far you can go into credit or debit, and that’s basically it – just numbers in accounts, and no money required. It’s a way for small businesses to support each other, and to survive in times of economic crisis.

What are the benefits of ‘small is beautiful’?

- We get better stuff – a move towards the hand-made, grown or built, and away from the mass-produced – so no more sweatshops, low-quality goods, unhealthy processed foods, pesticide-soaked monoculture fruit and veg, poor-quality clothes with toxic dyes etc.

- Helps end the left vs right battle that just supports corporate power; smallness involves principles of freedom, independence and responsibility beloved by the right and principles of unity, equality and mutual support beloved by the left – they are all fine principles.

- More interesting and creative jobs that promote independence, responsibility and dignity – with a revival in apprenticeships to learn fulfilling trades rather than supermarket shelf-stacking or telesales.

- Humans are happier in human-scale institutions and communities.

- Goods will be better value for money – although more expensive to begin with. However, if mass produced corporate goods carried the full price of the damaged lives and damaged environments that they cause, they would be much more expensive than locally-produced goods. We have to make our choices.

- Smallholdings and small farms produce more food per hectare than large monoculture farms.

- Helps solve the democracy problem directly.

- Stronger, safer communities, more interesting High Streets, unique localities.

- Corporations suck money out of local communities to pay distant shareholders, and ensure that we have to chase perpetual growth to give shareholders back more than they put in. The move from ‘one person, one vote’ to ‘one share, one vote’ is the true source of the lack of democracy in capitalism. And communism removes democracy by a more direct route.

- ‘Smallism’ can support a free market, but not the giant casino that is the global stock market, with huge financial rewards for bets placed rather than work done. ‘Small is beautiful’ is about rewards for work done to benefit one’s family, community and oneself. It’s not based on issuing shares to provide the investment to allow firms to grow, because growth is not the point. Business people own enough to run their business, not enough to dominate an industry, or to be as wealthy as a small country.

- Farmers own enough land to produce food for the local market and to support their families, not huge tracts of land that prevent other potential small farmers from having any. Land is the ultimate zero sum game. You can’t have any if I have it all.

- No business would be ‘too big to fail’, and require taxpayers’ money to bail them out.

- Smallness is good for employment; unemployment causes psychological and social problems, and if we’re sensible, is to be avoided at all costs.

What can I do?

First, read more on the subject. We provide books via a platform for small, independent bookshops – ‘small-ism’ in action. After that, you can support the principle with both your consumption and your production.

Consumption

If small businesses are to prosper there has to be a body of people prepared to support them by buying what they’re offering, rather than giving money to the corporate sector. So:

- use local shops, markets, independent restaurants, small businesses and co-ops rather than large supermarkets or chains;

- in those shops, try to buy goods produced locally and by small businesses, rather than large brands;

- use credit unions, building societies, and join a mutual credit scheme rather than using big banks;

- get a veg box delivery, or visit a farmers’ market to support local food producers.

With some products and services this will be difficult (cars, phones, laptops), but let’s do what we can now and see what develops. 3D printing may help obviate the need for large amounts of capital and huge factories.

Production

And of course, there has to be a range of local, small businesses for those people to buy from. So, why not start one?

If you just want to escape the rat race right now, but don’t have the skills or the ideas to start your own business, then go WWOOFing. You could get new ideas, gain new skills, meet new people who could help you change direction. Really, what’s the worst that could happen?

For each of our topics, we’re providing articles, links, courses, books, online courses and specialist advice on how to get going. You can do it for yourself first, then friends and family, and if you enjoy it, start to do it for your community. If people like what you do, consider trading via a local mutual credit network, where local producers commit to buy from each other (and if there isn’t one, contact us to talk about starting one).

We think it’s something we have to do ourselves, rather than waiting for governments that are corporate-controlled, and subsidise the corporate sector at every opportunity – ignoring their tax avoidance, inviting corporate leaders into government, accepting their money, talking to their lobbyists, introducing corporate-friendly legislation, bailing them out with taxpayers money if they fail. We can help reverse that. Of course it would be nice to have governments that would curb the power of big business, but under our corrupt political system with its obsession with growth, and the inability of (national) governments to control (international) corporations, that’s looking unlikely.

The views expressed here are those of the author and not necessarily lowimpact.org's

3 Comments

-

16degrees June 28th, 2021

Yesterday was Micro-, Small and Medium-sized Enterprises Day!

https://www.un.org/en/observances/micro-small-medium-businesses-day

-

2Dave Darby June 28th, 2021

*like*

-

3Esron Ndabitegereje April 18th, 2024

It is very helpful, I did this chapter when I was at University 2016 but the philosophy of small is beautiful is for the first time .they are many interesting things like the issue of capital intensive rather than labour intensive, as economics I 'm very understand the phenomenon of having a Capital intensive rather than labour within the courty when there is a big number of unemployed people like Rwanda our county .

Commons economy

Commons economy

Community

Community

Community-supported agriculture

Community-supported agriculture

Credit unions

Credit unions

Downshifting

Downshifting

Fairtrade

Fairtrade

Farmers’ markets / direct farm sales

Farmers’ markets / direct farm sales

Intentional communities

Intentional communities

Local / independent currencies

Local / independent currencies

Low-impact shopping

Low-impact shopping

Low-impact money

Low-impact money

Mutual credit

Mutual credit

Pattern language

Pattern language

Philosophy

Philosophy

Self-employment

Self-employment

Smallholding

Smallholding

The democracy problem

The democracy problem

Transition initiatives

Transition initiatives