That knotty problem: how to prune trees to produce quality timber

After reading the excellent article in Smallwoods magazine (issue 61) on formative pruning by Steve Woollard, I thought to build on that article with a perspective from a timber user.

As Steve outlines, formative and high pruning is an important part of a quality timber silvicultural system The pruning of side branches from selected trees within an area is probably the only way to ensure good form trees evenly spread throughout a woodland in lowland UK. It is desirable to rectify tree defects (forks) and remove lower branches to constrain the knotty timber within the core of a straight and tall tree.

Formative pruning

This is usually done from 5 years after planting. The idea is to remove major defects from selected trees within the plantation. These are usually caused by adverse weather (spring frost) or insect / mammalian attack, tree genetics, or wide planting spacing. The idea is to create a distinct leader that will give the tree a good start to producing a strong dominant leading shoot, and so go on to produce a straight tree. A straight tree is required to produce straight logs for efficient sawmill conversion and stable timber. Bends and sweeps in logs will produce timber that has internal stresses and so will spring (bow or bend) either during milling or drying. The photo below shows a 5-year-old Oak where one of the leading shoots will need to be removed.

High pruning

This is generally started in the early pole stage where the plantation canopy has closed and light competition is reducing the vigour of lower branches. The lower branches can then be removed, as they are no longer contributing to overall tree growth. Again it is worth noting that some species hang on to their dead branches interminably (Douglas Fir, Larch) and so these need to be removed to prevent dead knots reducing the quality of what would otherwise be clear timber. The almost legendary boat skin Larch and cricket bat Willow need to a absolutely clear of knots to fulfil their function. Imagine the chaos caused by small dead knots in the planks of a boat.

At this stage there may be other faults higher up in the tree. This is the time to try again and rectify these faults, bearing in mind the leaf area. As a general rule of thumb the crown should be 60% of the tree.

Photosynthetic area

It is important to allow the tree to continue to grow vigorously. For this to happen the tree needs as much leaf area as possible. When a major fork is removed it is advisable not to remove any further branches at that time. Other pruning operations can happen in future years when leaf area has increased. Interesting to note here that the allocation of photosynthate within a tree favours leaves and seeds, then shoots, then height above branches, and also that each branch needs to sustain itself from its own leaves.

Knots

A knot within timber can cause several major problems, these include:

- Structural strength. A knot is a weak point, and if a large knot is within a floor joist, fence rail, or tree stake, then it is more likely to fail.

- Drying defects. As timber is dried below fibre saturation point (nom. 25 to 30%) then the cells begin to shrink. At this point knots will not shrink as much as the surrounding timber. This will cause warping and winding within the drying boards and so degrade the timber. This is especially noticeable in kiln drying operations.

- Joinery defects. A joiner is unable to use timber that contains knots when making product that uses small sections. The knots would create weakness within the structure and movement within the article as it naturalises to the finished surroundings. Panels may crack, doors warp, furniture rails break, joints become loose. The photo below shows large live knots in a pine board.

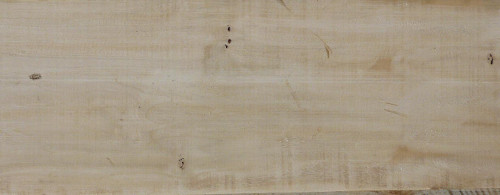

There are two main types of knot, a live knot and a dead one. The live knot is where the branch was living prior to felling and so the branch is part of the surrounding timber. A dead knot is a dead branch that has been grown around as the tree grows. This means that the knot is surrounded by dead bark and so is not part of the surrounding timber. Dead knots push or fall out of boards. Lem Putt goes into great detail about knot holes in privy doors in the book called The Specialist, where some prime example of God’s carelessness will always push the knot out. The photo below shows clear, knot-free timber, except for the small “cats paw” marking caused by epicormic small shoots.

For good building timber it is important to constrain the knots to a core around the pith, then the timber grown beyond this core is free from knots. Where formative pruning ends and high pruning begins is debatable as it may be necessary to remove a competing leading shoot even when the tree is quite tall at pole stage.

I would say the reason for formative pruning is to create as long and as straight a main stem as possible, and high pruning is to create that knotty core as small in diameter as possible (about 6 inches)

Spacing

So if you want to grow good building timber pruning is needed but it is not efficient to prune all the trees in a stand. You will know where the good form trees are, and also the other trees that can be “helped” along. Ideally these should be about 8 metres apart, leaving a matrix of other trees between to provide competition to encourage height growth of the selected trees. If there are particularly vigorous growing trees adjacent to a pruned tree it will be necessary to cut back these matrix trees to prevent excess crown competition. Final crop trees can be damaged by vigorous growth from invasive species like Birch, Cherry or Goat Willow so regular walks covering the whole area are required to monitor the situation. I remember a particular plantation where we were mixing formative and high pruning. It had been planted with groups of 5 to 7 Oak trees at about 10-metre spacing within a matrix of other tree species. Easy, just prune the best Oak in a group and move on to the next group.

Pruning cut

The pruning cut needs to be in the right place between the branch and the main stem. The branch collar is seen at this intersection, and this collar contains cells specifically designed to heal the wound made by branch removal. The photo below shows the collar, and pruning cuts should cut to the branch side of this collar, but leave no branch stub. Here’s a video detailing the healing process over several years when this branch was removed.

If the cut is not in the right place (either too deep or leaving a branch stub), then the tree cannot heal quickly and depending on species, rot can enter the tree. The next photo shows and ideal cut on the middle, and a poor cut higher up. In this case the operator has stood in the wrong place and cut the branch at an angle.

Species

Generally durable species (like Oak) will heal over large wounds up to 6 inches, but for non-durable species the maximum size of branch to prune for reliable healing is 2 inches, and for decay-risk species (Birch) even smaller.

Timing

The time of year is important to promote good healing. It is important to avoid the period when the sap is rising vigorously (late February to June) as this can lead to sap bleeding and damage to the bark under the wound (especially Sycamore). The other time to avoid is when the trees are entering dormancy. Some species need to be pruned in late summer, notably Cherry, to avoid canker and sliver leaf disease.

Andy Reynolds is a provider of free learning resources on YouTube, author of Timber for Building and Heating with Wood, forester and instructor, long-term practitioner in low-impact living, and tries to promote self-reliance wherever possible.

He teaches some of the eco-build courses for the Brighton Permaculture Trust.

This article was first published in the Spring 2017 of Smallwoods magazine

The views expressed in our blog are those of the author and not necessarily lowimpact.org's

Why self-reliance means being able to fix bits of old kit – like this circular saw

Why self-reliance means being able to fix bits of old kit – like this circular saw

Timber users and growers: what is ‘timber shake’ and why does it occur?

Timber users and growers: what is ‘timber shake’ and why does it occur?

What tree species to choose for woodlands in the 21st century

What tree species to choose for woodlands in the 21st century

Wood durability guide: timber durability chart & database

Wood durability guide: timber durability chart & database

How to source timber: a joiner’s point of view

How to source timber: a joiner’s point of view

Timber building

Timber building

Tree / woodland management

Tree / woodland management

Woodworking

Woodworking