Why pyrolysis and ‘plastic to fuels’ is not a solution to the plastics problem

Energy engineer Dr Andrew Rollinson sets out the case as to why pyrolysis and ‘plastic to fuels’ is not a sustainable solution to the plastics problem.

Compounded by the breakdown of the global recycling market, it seems that most governments and local authorities throughout the world are grasping at straws to find a quick fix for the plastic waste problem. Plastic is piling up on land and threatening the biosphere through its contamination of the oceans. At the same time most governments exhibit a morbid fear of doing anything which could oppose continuous economic growth.

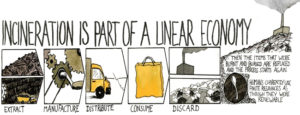

Wonder technology fixes such as pyrolysis for ‘plastic to fuels’ (1) and green energy from waste (EfW) are therefore offered up as the future solution. For, if such machines were capable of simply and sustainably converting plastic into fuel or energy, then citizens may feel encouraged to buy more and waste more, liberated from guilt with the knowledge that anything they saw and wanted could be purchased.

But this premise is inherently flawed. Pyrolysis of plastic can never be sustainable. In a recent academic journal, I detail why the concept is thermodynamically unproven, practically implausible, and environmentally unsound (2).

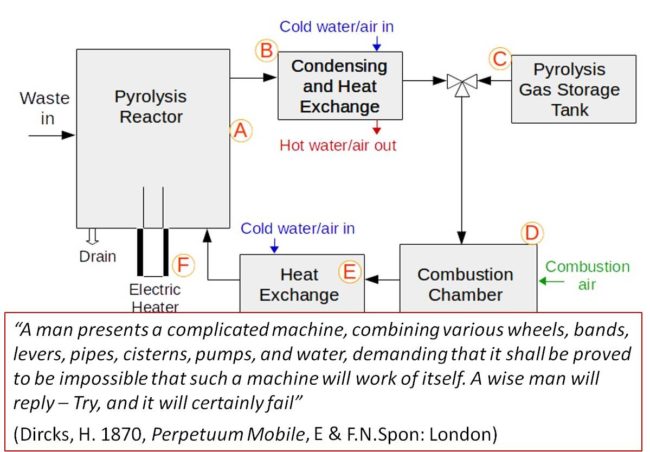

Pyrolysis occurs when solid organic matter is heated, resulting in the release of gases, oils, and char, hence the word’s etymological root of “loosening or change by fire”. It is an old technology, formerly applied by heating up wood to produce substances such as methanol, acetone, and creosote, prior to petrochemical refining routes. When wood is slowly pyrolysed the char is called ‘charcoal’; when coal is pyrolysed the char is called ‘coke’; and with plastics there is little or no char produced at all.

The modern notion is to pyrolyse plastic (and other municipal refuse) into a gas or oil which is then useable as a commodity, invariably a “fuel”, in its own right. This conveniently ignores the fact that pyrolysis is an energy consuming process: more energy has to be put in to treat the waste than can actually be recovered. It can never be sustainable.

And what of the fuel from these ill-conceived schemes? All pyrolysis EfW or ‘plastic to fuels’ products must be combusted to liberate energy, thus releasing the same quantity of carbon dioxide than if the plastic had been incinerated directly. The product’s existence has merely been an intermediary stage in the combustion of fossil fuels.

But the idea is even more imprudent. There are substantial flaws with the pyrolysis of plastics concept. It has been tacit knowledge for almost one hundred years that this type of waste is practically incompatible with these technologies (3). Also, heavy metals and dioxins become concentrated in the resulting products making then unsuitable as fuels, because when combusted they are released to the environment.

Despite this many governments continue to waste millions deceiving the public in pursuit of an ‘innovation’ that holds the sustainable answer. They ignore the above-mentioned scientific antecedents, and a wake of commercial failures (4).

Academic research has also been drawn in, attracted by the competition for financial rewards. With a prevalence in many countries for grant funding which links industry, innovation, and academic research, ethical hazards have been created and these have yielded poisoned fruit (2).

Many modern academic research articles present pyrolysis with positive connotations, appraising it in terms of “energy recovery” or “conversion” efficiencies. This is despite huge overall energy demands. In one study the concept was described as “high efficiency”, but results showed that the system operated with gross negative efficiencies, using between 5 and 87 times more energy than could be obtainable from the pyrolysis products.

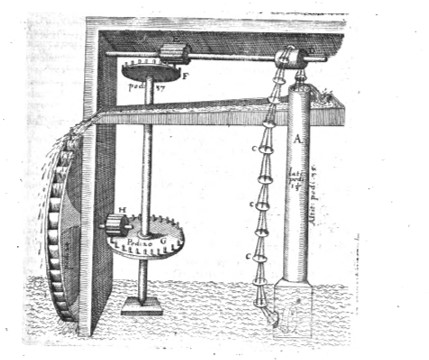

Perhaps worst of all, some research groups have recently claimed that pyrolysis plants can be self-sustaining. By doing so they commit a blunder which exposes them to instant discredit, for they ignore the second law of thermodynamics. Such a folly is akin to the antiquated pursuit of perpetual motion.

Perpetual motion is impossible because it violates the laws of thermodynamics. These laws underpin all engineering, and indeed all universal interactions. The first law states that energy must be conserved – what goes in must come out. The second law states that whenever there is energy transfer some quantity must always be lost to a system’s surroundings (measured as “entropy”).

The inviolable nature of the second law was perhaps best explained by Arthur Eddington in his famous Gifford Lectures (5):

“There are other laws which we have strong reason to believe in, and we feel that a hypothesis which violates them is highly improbable; but the improbability is vague and does not confront us as a paralysing array of figures, whereas the chance against a breach of the second law can be stated in figures which are overwhelming.”

Once one fully understands these laws, the folly of such schemes, and the sophistry of corporate attempts to claim “sustainability”, becomes instantly clear. It is therefore essential to grasp this concept if ever humanity is to make a transition to a sustainable future.

Pyrolysis can never be a sustainable answer to the inconvenient truth of Big Plastic. This lies in the widespread implementation of strategies for “reduction” and “re-use”, along with a preference for creating products with in-built recyclability and/or which are built to last. The elephant in the room is capitalism (6) and the throwaway culture that the present version of this economic system has created – ever demanding new markets, more sales, more consumption, and more waste.

The full text of the paper can be accessed for free here in Resources, Conservation and Recycling until 23rd December 2018.

1. Phan, A. How we can turn plastic waste into green energy. The Conversation, 1st October 2018.

2. Rollinson, A., Oladejo, J.M. 2019. ‘Patented blunderings’, efficiency awareness, and self-sustainability claims in the pyrolysis energy from waste sector. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 141, pp. 233-242.

3. Mavropoulos, A. 2012. History of Gasification of Municipal Solid Waste through the eyes of Mr Hakan Rylander (online), 19th April 2012.

4. Tangri, N., Wilson, M. 2017. Waste gasification and pyrolysis: high risk, low yield processes for waste management. A technology risk analysis (online).

5. Eddington, A.S., The Nature of the Physical World, 1927. Cambridge University Press: London. pp.68-71.

6. Pigott, A. Capitalism is killing the world’s wildlife populations, not ‘humanity’. The Conversation, 1st November 2018.

Doctor Andrew Rollinson specialises in small-scale biomass gasification research and is the author of Gasification: succeeding with small-scale systems published by Lowimpact.org.

The views expressed in our blog are those of the author and not necessarily lowimpact.org's

118 Comments

-

1J Socci February 28th, 2019

The paper referenced by A. Rollinson that discusses whether prolysis plants can be self-sustaining refers to MSW as a feedstock. Here the author is referring to plastic wastes as a feedstock, which will have much higher heating values (more energy), therefore the energy balance will be completely different.

-

2Andrew Rollinson February 28th, 2019

Dear J Socci,

I am the author of both articles.

My journal paper covered pyrolysis of MSW (and sewage sludge – literally a MSW, though not often categorised as such). Plastic is a high component of MSW for most countries, so the reference to plastics here is relevant. Indeed, my journal paper specifically referred to the extra problems of plastic pyrolysis, namely: the amorphous nature of the plastic hydrocarbons meaning that usually zero char can be produced (relevant because char usually has the highest energy density of the three pyrolysis product phases), and that dioxins concentrate in the pyrolysis oils.

Pure plastic will have a higher energy density than raw MSW, but the fact is inescapable that to pyrolyse this material requires energy. In my paper I show that the energy produced in the pyrolysis gas and oil is less than the energy needed to pyrolyse it (enthalpy for pyrolysis) along with the entropic losses and auxilliary electricity associated with the concept of this type of plant.

Of course there was another theme to my journal paper, and this blog, which is the absence of satisfactory energy balances when these technologies are presented. Some don’t even mention the need for energy inputs at all while simultaneously claiming that their process is “sustainable”. I absolutely include “plastics to fuels” in that category.

Andrew

-

3J Socci February 28th, 2019

Why are you bothered about the production of char from plastics when the hydrocarbon gases are readily combustible to provide energy for the process? There are understandable issues surrounding the toxic byproducts generated by the pyrolysis of certain plastics, this can be negated through proper feedstock selection.

I don’t think you provide any tangible figures referencing energy balance values. A paper on the energy balance of a 1kg/h test rig (https://dx.doi.org/10.5541/ijot.5000147483) calculates that for beech wood all the energy losses for the process equates to only 6.5 % on HHV basis. Plastic generally has a much higher HHV than biomass, therefore it would be expected the combustion of the produced non-condensable gases would provide more than enough energy to drive the process. I do agree that there are some reasonable environmental considerations for the pyrolysis of plastics, but the pyrolysis of pure plastic waste and MSW is very different.

-

4Andrew Rollinson February 28th, 2019

I mentioned char because it is the most energy dense of the three pyrolysis products. Many of the proposed waste pyrolysis concepts claim to make use of char to heat the retort. It is just not feasible.

Do you have any evidence of a pyrolysis of waste plant where (as you say) “the hydrocarbon gases are readily combustible to provide energy for the process”. I’d like to see that evidence please of such an operational plant. It is no good saying “…would be expected…” and “…would provide…” Such claims constitute the crux of my paper.

Thanks for the link to the test rig fed with beech wood. I’ll read it over the weekend.

Andrew

-

5Andrew Rollinson February 28th, 2019

I’ve just had a quick look at that beech wood test rig paper on fast pyrolysis. Here is what Tony Bridgwater said about fast pyrolysis in 2012:

“The by-product gas only contains about 5% of the energy in the feed and this is not sufficient for pyrolysis” (Biomass and Bioenergy, 38, pp.68-94).

By the way, I’ve met Tony a couple of times. A nice man. And, I am friends with a couple of people in his group at Aston. We probably agree that pyrolysis has a niche and is an interesting technology. I just want there to be more transparency on its practical utility and energy demands, for many people are passing it off as being a sustainable solution to waste. It isn’t.

-

6J Socci February 28th, 2019

Yes, he is my supervisor! You now have another friend in his group at Aston! ?

I guess that paper is talking about fast pyrolysis of biomass, in which case the major product is organic liquid yield and the gas in mainly composed of CO and CO2. My point is when pyrolysing plastics, depending on process parameters, there will be a high yield of combustible hydrocarbon gases (alkanes and alkenes), as well as a liquid fraction. So I think to compare plastic pyrolysis to a perpetual motion machine is misleading.

Totally agree, and I think proponents of pyrolysis often overlook the high CO and CO2 yields, however, pyrolysis may be a better alternative to incineration which a large proportion of waste is subjected to currently.

Cheers

Joe

-

7Mark F. Martino March 8th, 2019

I’m only a mediocre engineer who hasn’t designed anything in years so I appreciate your indulgence with my musing and any suggestions.

While plastics cause a lot of trouble, they are not going away for a while and there is a lot out there. Even if the energy in is more than the energy out, there is a way to make plastic pyrolysis viable. If homes, apartments, and businesses had there own pyrolysis units, they could convert their waste into energy on site. The syngas could be used to generate electricity directly. This would save the energy used to transport and sort the waste. It also prevents the pollution from the vehicles transporting the waste. And maybe other waste could be processed.

-

8Andrew Rollinson March 11th, 2019

Dear Mark,

There are practical problems with domestic pyrolysis of waste/plastics machines. These relate to heat losses from the reactor during feeding, corrosion and erosion caused by the high ash and chlorine content, removing ash (and again having to maintain high internal temperature in the reactor while doing this), and the tarry nature of the pyrolysis gas which sticks to downstream components necessitating system shutdown for repeated cleaning. All these relate to pyrolysis on any scale.

The above are reasons why the concept of a domestic pyrolysis reactor is an impractical pipe dream. Yet, surprisingly, you will find people promoting that they have developed the concept…. and seeking naive investors for the gadget that is the answer to all domestic waste. Avoid these people.

Notwithstanding the practical aspects above, let me explain again about the energy balance: The practical aspects do impact on the energy balance because each time the reactor is opened to feed or to clean, the internal temperature cools down, this demands greater energy input and also dramatically changes the chemistry of the gas and oils that are produced. But, let us assume that you can discount them and that you have heated up your reactor containing plastic:

Assuming that you had heated your reactor up to 550C. This cost you 10 kWh of electricity. You then need to pyrolyse all the plastic, and this will cost you a further 3kWh of electricity, then the gas and oil is burned in an adjacent combustion chamber where it heats water and the water is used to turn a generator so that in total you can produce 5kWh of electricity. Overall you have disposed of your plastic at a cost to you of 8kWh. This could be electricity from the grid or your battery bank.

These are NOT renewable energy devices.

Yes, it seems ideal to be able to convert your domestic waste into energy in a kitchen appliance type gadget, but fundamental universal laws dictate that it is not possible. The idea is, as I have said, akin to the antiquated pursuit of perpetual motion.

Andrew

-

9Andrew Rollinson March 11th, 2019

Dear Mark,

I’ve just re-read your post, and I believe that I perhaps haven’t answered it:

Yes, IF the systems could be made to work, and IF one is willing to pay high energy costs for melting plastic at home, then it would obviate having to transport and sort the waste on a regional level, and would remove some vehicular pollution.

The corporate-sector waste contractors who have locked-in local authorities to supplying them with municipal waste for a term of 25 years would probably have something to say about it.

-

10Mark F. Martino March 11th, 2019

Dear Andrew,

Thank you for filling in details of my understanding of the pyrolysis of plastic, especially the numbers you included in your explanation. I thought I had found a pretty good approximation of a solution when I discovered the Dung Beetle project in Africa, which involves a portable pyrolysis unit. I can see how it has the problems you pointed out. So, even at a small, controlled scale, pyrolysis is not the way to dispose of plastic or other kinds of trash.

I appreciate the research and work you are doing and hope there is another solution beyond recycling and composting. Here in Kirkland, Washington, we’ve been recycling for decades, but there always seems to be massive amounts of plastic and other trash that cannot be recycled. Instead, it goes to a collection site about a half mile from my home. From there, trucks haul it to a railroad station where it is loaded onto railroad cars and taken to a landfill in Oregon. I watched this happen for many years. It really seemed to me that the local pyrolysis of the trash in small, discrete batches had to use less energy and cause less pollution than that. Thank you for showing me why we need to pursue other solutions.

-

11Wally March 22nd, 2019

I wouldn’t even go as far as to say I know something about this topic. But I do have a question. Using tires and plastics to create a diesel fuel, although it requires a lot of energy to do. Wouldn’t it still help to solve a problem that has to be dealt with? Doing something with waste. Or is it only moving the problem to another area?

-

12Andrew Rollinson March 26th, 2019

Dear Wally,

True, it would “do something” with the waste. Some people attempt to pass this of as being sustainable, but it isn’t.

-

13Zhao Zhang April 1st, 2019

An impressive paper by Dr. A.

I resolutely oppose small pyrolysis systems in your home, your backyard or in the community as it maybe encouraged.

Small pyrolysis systems are often open systems without any tail gas treatment. They may bring problems of serve air pollution as the pyrolysis gases often contains PAHs, N-PAHs, HCN, CO, etc. In a open system, these gases can be easily leak to the air and cannot fully converted in the combustion systems.

When I saw the small pyrolysis systems making biochar in household, I was very sad.

These systems discharge a lot of dark smoke, but the farmers thought they are saving the world. When we talk about the carbon negative of Biochar, has anyone thought the emmission of Black carbon and brown carbon?

Many thanks to Dr. A for the critical review, which reveal the truth of this field.

-

14John Whitby June 5th, 2019

Not about pyrolysis, but regarding the plastic waste problem.

Is there any reason why the heavier grade plastics (milk containers, bottles, food containers up to hard plastics), couldn’t be shredded and then compressed into blocks or panels using either a resin or cement type binder. The thermal insulation properties of these blocks should at least equal that of cinder blocks, making a strong thermally efficient building system at a reasonable cost, whilst recycling huge amounts of plastic waste. In fact you could pre-bond the insulation and timber frames to the panels, meaning the only extra work needed would be fitting the plasterboard and skimming.

Depending on the construction, as pre-compressed panels, they would certainly be suitable for fast-build, lightweight single story dwellings (even the roof tiles could be made from the same type of material, just of thinner construction), and probably two storey dwellings also.

-

15Mike July 6th, 2019

I understand this is an old article but I recently read about a plant in Japan which claims to be producing net energy from plastic waste while meeting high emission standards. I wonder if the author of this article would mind commenting on this plant.

I found a video with the details here – https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=620&v=KKTAdZFc-ss

No doubt the creators of the video are highly biased, but they are claiming 4MWe of electricity is being exported to the grid and almost 9 million litres of oil being reclaimed from plastic waste, along with solid fuel and hydrochloric acid.

-

16Andrew Rollinson July 9th, 2019

Dear Mike,

I watched the Youtube film all the way through. I didn’t see or hear any mention of the plant claiming to operate using only the energy available in its plastic waste products. There was one statement about something called a “normal pressure separator” using oil from the plant.

I strongly maintain that it is impossible for plants such as this to function wholly from the energy contained in the products that come out of their processing line.

Andrew

-

17Grace July 9th, 2019

Hi Andrew

Just chanced upon this, its a great read and thank you so much for your insights in pyrolysis space.

I was just wondering if you could share with the full text of the paper here with me, unfortunately, i only chanced upon this article after the deadline.

Many thanks

Grace

-

18Andrew Rollinson July 9th, 2019

Dear Grace,

I have just sent you a pre-print version by e-mail.

Best wishes,

Andrew

-

19Anton July 12th, 2019

What utter nonsense! Pyrolysis can be self sustaining I wonder if the author ever built a pyrolysis plant?? This article is testimony of his lack of knowledge on the science. I suggest he come and visit us so he can be educated before he shoots off his mouth on subjects he knows nothing about.www.recor.co.za

-

20Dave Darby July 13th, 2019

fight, fight, fight, fight

Lack of content there though Anton. Could you focus on something he said that you think is wrong, and why, then he can answer your point. At the moment, you haven’t made any.

-

21Dan Esterhuyse July 13th, 2019

Correct Anton. Just bullshitting the uninformed.

-

22Dave Darby July 13th, 2019

Dan – you sound like one of those kids who hide behind the bully, shout insults and run off. Make a point, and back it up with something.

-

23Henry Raymond July 13th, 2019

I have to say I disagree to some extent with these conclusions. First, pyrolysis cannot only be done with plastic but many other feedstocks so the idea that it is unsustainable is questionable in my opinion. Secondly, plastic is and has been is use for decades and so there is plenty of it available. It is unlikely to go way anytime soon. Plastic bottles, food containers, milk jugs, oil, detergent, and many, many other products are sold this way and some areas do have recycling programs for pickup already. The main observation seems to be that the process uses more energy on analysis than is generated by it. This assumes that you are using electricity to heat the mass. Some energy can be obtained from the process itself by burning the gasses that are generated from the breakdown either of plastic or biomass. No mention is made however of solar power which is readily available in many parts of the country particularly in summer or the use of wind power. Both of these, once the original capital costs have been absorbed basically generate free power. Even hydroelectric power could be used AND most importantly it is difficult to store energy except where it is being converted to liquid fuel. Pyrolysis in my opinion does provide an answer to alleviating our massive pollution problem with plastic and bio waste etc., and it is converted to liquid fuel which can be transported. Remember, fossil fuels aren’t free either.

-

24Andrew Rollinson July 15th, 2019

Dear Henry,

Pyrolysis is wood can be sustainable if the wood is from sustainably managed forest, but it will still be a process that uses energy. Additional wood is burned to drive the process. One would need to plant trees to replace those used for pyrolysis and more trees for those burned to drive it.

Pyrolysis of plastics cannot be sustainable because the plastics are made from oil. Ultimately the products that are created are burned to release energy and ultimately the same amount of CO2 as if the oil had been burned directly. On top of this more fuel (oil, wood), needs to be burned to drive the process. Therefore, the process is not, and can never be, sustainable. It is more of the same for increasing energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions

Wind turbines and solar panels could not drive the pyrolysis process as they do not generate sufficient energy for long enough. Anything that heats up (irons, cookers, tumble dryers, kettles) needs tremendous amounts of energy in comparison to, say, light bulbs, computers, radios. Pyrolysis is a process of heating up and therefore in the former category, but it also needs sustained and high temperatures for long periods. It is very energy intensive.

I am a gasification engineer, who has also worked with pyrolysis (but the two are similar processes). Anyone who has worked with these systems will know the truth of what I have described above. It is fundamental. I wrote the journal article, and this blog, because “entrepreneurs” and quack scientists/engineers (who by the way were attracted by government funding), along with unscrupulous consultants, were trying to pass off these systems as being sustainable. They were baffling planning and permitting officers, higher-level decision makers, and targetting ethical investors who in turn were losing their savings. See for example reference number 4 in the blog and also this: http://www.ukwin.org.uk/files/pdf/UKWIN_Gasification_Failures_Briefing.pdf

There are also inherent problems with practically implementing pyrolysis of waste/plastics. I have written enough already, but the details are in my journal article with explanations and case studies. This also is fundamental to anyone who has operated these systems.

Andrew

-

25Andrew Rollinson July 15th, 2019

Sorry. This should start: “Pyrolysis OF wood…”

-

26WillRau July 18th, 2019

Andrew – I also have come to this discussion late. Could I also please have a copy of the full text paper? Thank you in advance.

-Will

-

27Andrew Rollinson July 19th, 2019

Certainly Will.I have just sent you a copy.

Andrew

-

28purist thundewrath July 23rd, 2019

Hi,Andrew,what about tires,I see they get shredded and used elsewhere.would it be financially feasible to microwave pyrolysis them into fuel.for me it seems more productive to use all stored energy in them to power actual vehicles or plants instead burning straight up after shredding.

Ps. I’m uneducated pleb ,enlighten my dark mind with some powerful knowledge ?

-

29Andrew Rollinson July 24th, 2019

Dear purist,

You pose your question in a way that is interesting and revealing about both the current societal mindset and prevailing misunderstandings with respect of efficiency and sustainability. You ask, is it “financially feasible to microwave pyrolysis [tyres]”. My answer is “yes, it may be”. Governments financially support these ventures to make them financially feasible. But, financial feasibility has absolutely no correlation between engineering efficiency nor resource or ecological sustainability.

Tyres are made from petroleum and to convert them to fuels ultimately means to burn them since burning a fuel is the only way to release its energy into a useful form. Therefore it is more of the same in terms of greenhouse gas emissions. The petroleum has merely spent a part of its existence as a tyre rather than being burnt directly.

Notwithstanding the above, the perceived benefit of recycling tyres into fuel is that it offsets using virgin petroleum. But this notion is completely undermined when one considers that enormous amounts of extra fossil fuels (coal, petroleum oil) have to be consumed to process the tyres in this way. Solar panels and wind turbines will not provide the amount of energy required for this. The proposal to use microwaves is particularly energy intensive and dangerous. There is the energy needed to finely shred the tyres, then mix them with metal catalyst (which has been known to cause a fire hazard during the pyrolysis process), but more importantly it is the energy needed for pyrolysis. It was with microwave pyrolysis that I referred to in my blog as consuming 5 to 87 times more energy than could be obtainable from the pyrolysis product (a study which – despite the gross negative efficiencies – was described as “high efficiency” by the way). Another study, not mentioned in the blog, operated with 18 to 21 times negative efficiency for the same reasons.

Andrew

-

30Christine Mayles July 28th, 2019

Hi Andrew. Thank you for your article. Whilst the process is not a sustainable solution to the plastics problem, do you not think that perhaps it has a place? My belief is that to tackle the worlds waste problems involves a many pronged attack. In our money orientated society I believe hitting business and the general public in the pocket is the way to change the capitalist and throw away culture (needless to say I wouldn’t be voted in as a politician any time soon!) That said the UKs packaging waste regulations became a toothless tax that many financially affluent businesses just paid off and changed nothing, so any legislative changes would need to be robust and policed. Plus if people had to pay more for their plastic waste to be removed I believe the general public would be less inclined to purchase items containing it (fly tipping aside of course!).

The pyrolysis solution would have a place to recycle that which still remains whilst not giving people the false representation that plastic is now guilt free. Whilst it is not a perfect solution at present, it would be nice to see government investment in improving the technology for renewable energies and the technologies for the efficient processing of waste for the future.

And yes I am a waste reduction obsessed optimist!

-

31JD July 28th, 2019

Greetings.

My local municipality is looking to implementing pyrolysis as a means to combat the plastic waste problem. They’re mostly clueless in regards to environmental concerns, and think that implementing this is a solution to our plastic waste problem. Is there any way I can see your paper, or receive it in email, so that I can use it to highlight the potential drawbacks during municipal sessions? I don’t want them to think that this is a magical solution.

-

32Andrew Rollinson July 29th, 2019

Dear JD,

For you and any others who may be interested, here should be a link to the pre-print version of my full journal paper – http://blushfulearth.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Manuscript.pdf

Please let me know if it doesn’t work.

The circumstances you describe about your local authority are sadly commonplace. It will end in failure, abandonment lost investments, and likely a risk of toxic waste by-products if it ever gets to the stage where it is built. People may seem indifferent to local authorities losing investments but such folly obviously has a direct impact on service provision.

Dear Christine,

No, I do not think that pyrolysis of plastic has a place in a transition to a sustainable future. Pyrolysis and gasification technology, fed with horticultural waste and arborial off-cuts from sustainably managed land does have a place. Plastics pyrolysis does not, for the reasons that I have described.

All energy from waste is down at second from bottom of the waste hierarchy for good reason. We need to reduce and re-use materials and/or create them with inbuilt recyclability. Single-use plastics need to be banned.

Andrew

-

33JD July 29th, 2019

The Philippines actually, which is the 3rd worst plastic polluting country into our oceans, sadly. We need to do something but I think they’re just grasping for answers blindly without thinking things through.

-

34Andrew Rollinson July 29th, 2019

Dear JD,

Yes, I am aware of the situation. Governments and local authorities don’t know what to do, and they are under enormous pressure from entrepreneurs who come to them saying that they have a technology which can be a silver bullet to plastic waste.

Andrew

-

35Mike McKeen July 30th, 2019

Has there been any investigation into the use of solar thermal as a source for process heat? I live near the Ivanpah Valley solar power station, but I know that they use a considerable amount of natural gas in order to keep the plant running 24/7 and to avoid wasting the early morning and evening sun to preheat. But what if it were used to pyrolize plastics instead of heating water for electricity? Of course, the economics require a rather expensive solar thermal array be constructed as the temperatures are not trivial, but I was more thinking about the thermodynamics of the system. Rather than a more energy intensive source like gas or electricity, would a concentrating array give the needed temps at a rate quick enough to make production worthwhile?

-

36Andrew Rollinson July 31st, 2019

Dear Mike,

Thanks for your comment.

Large-scale solar thermal concentrators like the one at Ivanpah Valley would definitely generate a sufficient level of temperature for pyrolysis.Of course, this is purely theoretical.

Interesting about natural gas being used to supplement the facility. This is done with large-scale wind turbines linked to the grid in the UK. Here we now burn mostly natural gas for this reason due to the short-start up times of these large-scale fossil fuel power plants. I often tell people who advocate for grid-tied wind power that they are actually supporting the burning of fossil fuels and in particular (fracking) shale gas, but they generally don’t comprehend this. Why? Because it is another area where education is needed and where the government needs to “tell the truth” (as Extinction Rebellion demand).

Back onto topic – I was just hearing about how shale gas in the US is driving forward an exponential increase in plastics production in your country, due to how cheap it is. Natural gas/shale gas is the reagent for plastics production.

Andrew

-

37Sunil Chunduru August 9th, 2019

Hi,Andrew

I am an undergraduate student working on converting plastic to electricity in that I need use pyrolysis of plastic to generate gases.By reading your article on pyrolysis is not sustainable to plastic.I need to know is there any efficient methods for converting plastic into gases other than pyrolysis. Please let me know

-

38Andrew Rollinson August 11th, 2019

Dear Sunil,

No, I don’t know of any.

Andrew

-

39Bui Hoang Linh August 16th, 2019

Article claims: Pyrolysis is net negative energy production

Fact: You burn a plastic bag, it continues to burn without having to supply power

How can I get extra energy from a proclaimed to be net negative energy production?

-

40Andrew Rollinson August 19th, 2019

Dear Bui,

It is difficult for me to understand your comment. Are you perhaps asking why when try to burn a plastic bag it melts and gives off heat, and isn’t this therefore proof that the process can be energy positive? If so, “no”, you are confused:

Pyrolysis is not the same as burning. With pyrolysis you are excluding oxygen. It is an endothermic (heat must be continuously added) process.

With combustion the process is exothermic (heat released). Though there needs to be an ignition source to get the reaction to proceed (so some input of energy), it can (if the material is dry enough, and if the reactor is configured such that oxygen is completely mixed through the feedstock, and if ashes are satisfactorily and continuously removed) proceed spontaneously because of the freely available oxygen. And, it may then yield surplus heat, so be net energy positive. This combustion process description is the principle of incineration. For multiple reasons relating to the feedstock composition and practicalities of processing the waste, net plant efficiency is very low at ca. 10 to 30%, with the very high end only for very large plants.

What I am saying therefore is that the notion to batch process plastic and other mixed wastes by pyrolysis, i.e. the need to detach the pyrolysis stage from the combustion stage and drive this by externally supplied energy, added to which are the numerous challenges of feeding, transferring the gases post processing, cleaning the gases, maintaining the necessary high temperatures (all of which also use energy), push the energy balance into the negative. Case studies have shown this, and my new research has shown this. It cannot be sustainable. At a simplistic level, and discounting for now some of the other process challenges, what you are suggesting is the error made by many others in that you fail to consider the second law of thermodynamics which must incur greater inefficiencies when you add all the extra and necessary process stages.

Andrew

-

41Joshua August 23rd, 2019

As far as thermodynamics go and the pyrolysis heat output, I’m looking at transferring the heat out put into steam energy. Maybe in multiple layers? I’m mainly commenting so I can come back to this later.

-

42Mik Fielding August 27th, 2019

The big point about this is not whether it is a sustainable practice as such, we really do need to seriously cut down on plastic usage, but this could go a long way toward dealing with all of our current waste along with future waste until we find alternatives.

-

43PT11 August 28th, 2019

Great article and comments. I you make a clear argument that pyrolysis is net negative energy so not a sustainable practice.

Without denying that fact is there still any value in plastic pyrolysis as a way to dispose of single use plastics that would otherwise go in a landfill or the ocean?

I like the idea of banning single use plastic but I don’t see it happening any time soon and meanwhile massive amounts of plastic waste are being generated that will never be recycled. Basically anything except bottles.

Could it be worth the extra energy cost to destroy this kind of waste? I imagine something like a hospital with massive amounts of single use plastic waste that will never be recycled and might also have some kind of toxicity that should be incinerated anyway?

-

44Andrew Rollinson August 29th, 2019

Dear Mik,

All energy from waste technologies propagate the business as usual, “make-use-discard”, linear economy. This is why unprogressive governments fund them, despite the fact that they are down at the bottom of the waste hierarchy. See: https://www.lowimpact.org/corporate-goldrush-incineration-gasification-pyrolysis-waste-generates-consumption-waste-pollution/

You say “…until we find alternatives…” When we are rapidly heading for the cliff edge, is it sensible to put effort into a concept that doesn’t work, has been known to science for over one hundred years to not work with mixed waste, uses more energy than it yields, creates toxic by-products, and locks us in on the same trajectory?

Andrew

-

45Andrew Rollinson August 29th, 2019

Dear PT11,

Hospital waste is incinerated for that reason. Probably it is the best available technique.

As mentioned previously, and notwithstanding the net negative efficiency, I don’t think that plastic pyrolysis is the answer – definitely not the solution that it is made out to be for multiple practical reasons. My opinion is that we need to tell the truth and attack the root cause.

Thanks for your kind comments about the blog.

Andrew

-

46Mik Fielding August 29th, 2019

It does seem that people are missing the point on this.

The fact is that we have millions of tons of plastic waste and no other viable way of disposing it without causing a lot of other pollution. There are lots of diesel and petrol (gasoline) powered vehicles on the road and plenty of ships that use heavy oil. These are not going to disappear overnight, so they will continue to pollute for a number of years yet.

By breaking down the plastics and using them as fuel, we can get rid of it without creating any more pollution than is already ongoing.

Quite clearly we need to stop creating the waste, but that will also take time, so to criticise and dismiss this technology because it isn’t part of the long term sustainability that we need to work toward is just being very petty.

I have spent a large part of my life over the last four decades or so promoting and researching sustainable solutions and so often find people dismissing something because it is not the perfect ultimate solution. Such a thing does not exist and we have to gradually work through many interim stages to reach those solutions that are viable in the long term.

This is certainly better as an interim use as fuel that much of what is bandied about as ‘biofuel’ made from palm oil grown by hacking down ancient forests to create fuel that is not really much, if any, cleaner than the fossil fuel version. Until we reach entirely electric vehicles, whether battery powered or hydrogen fuel cell powered, with the energy coming from renewable sources, then we may as well make the most of converting the plastic waste to fuel and help solve one of our biggest problems.

Of course it isn’t a long term sustainable solution, but until we have that it can be of great use …

-

47Andrew Rollinson August 30th, 2019

Dear Mik,

My motive for writing the journal article upon which this blog was based comes from the fact that many people are trying to pass of the pyroysis of mixed waste and plastics concept as sustainable, and some scientists/engineers are even making the foolish “mistake” of suggesting that they can be self-sustaining on the gas they they produce. I hope that you do not think that I was being petty. I have made these systems the focus of my work for the last ten years. Pyrolysis and gasification – when fed with sustainably managed woody off-cuts and agricultural waste – definitely have a niche for society’s transition to a sustainable future. We must not however be deluded about what these systems can and cannot do, and if society is to transition to a sustainable future then we must “tell the truth”, as I quoted earlier with reference to Extinction Rebellion.

Mixed waste (often described as MSW) pyrolysis is a non-started for practical/technical reasons, even if you accept the fact that it won’t be self-sustaining and that it will consume rather then yield energy. This will not be remedied in the foreseeable future, as much as many people would wish that such a black box for waste disposal could exist. That, unfortunately, is the inconvenient truth.

What have recently been called “plastics to fuels” concepts – using specific types of plastic only – are energy intensive chemical process plants which propose to use pyrolysis reactors. Time will tell if they can be made to work (again notwithstanding the fact that they are energy intensive). I personally don’t think that we have that time.

Andrew

-

48Mik Fielding August 30th, 2019

Dear Andrew

I get what you are saying and I know there are plenty of folks who would use this merely as an excuse to claim it is sustainable, where we both know it isn’t, but do you have a better idea about what we can do with the mountains of plastic waste that needs dealing with?

We certainly don’t have much time at all …

-

49Andrew Rollinson August 31st, 2019

Dear Mik,

Ban single-use plastics. Use biodegradable alternatives.

Governments must legislate. It must be a top-down approach.

Andrew

-

50Mik Fielding August 31st, 2019

Andrew, that is completely obvious my friend, but this doesn’t answer the question about what we can do with the mountains of existing plastic waste that needs dealing with?

Not to mention the mountains of it yet to be produced by the time all of the governments have banned it. Considering that they are generally at the beck and call of industry lobbyists who will be pushing them in the other direction! I can’t see the likes of Donald Trump or the UK Tories jumping in to legislate too quickly, not to mention China, India and every other country.

Sorry, but I am a realist, I have been fighting the good fight for over four and a half decades and in is frustrating and infuriating how long it takes to shift things.

Meanwhile, the mountain grows and more and more ends up in the environment. What do we do with it?

I read about plastic waste being used to make roads, they were using it in the tar I think. They were making great claims of how better the roads were that conventional ones, but all I could think of was as they wear and all of the microplastic particles being shed into the environment, blown into the atmosphere by the winds and washed into the drainage and eventually into the rivers and sea.

Pyrolysis may not be the best or the only way and, as people need to understand, it doesn’t make anything sustainable, but surely it is one of the tools that can be used to deal with the problem. It should not be discarded because it isn’t a mythical ‘perfect’ solution. None of them are …

-

51Andrew Rollinson September 2nd, 2019

Dear Mik,

I have been described as “contemptuous” recently. If what I am about to write seems contemptuous of your comments, then I apologise. It is not intended to be, as I actually agree with what you say. In mitigation I say that I write this way because I believe that no longer must scientists and engineers compromise on the truth (to play their version of this toxic system’s game – e.g. to protect their careers and acquire perpetual grant funding) if society is to survive what lies ahead. So:

I have explained that pyrolysis of MSW cannot work, I have logically explained that the concept is inherently unsustainable, I have evidenced how it locks us into the same “business as usual” trajectory which has got us into this mess in the first place – hence producing more plastic and more waste, I have also told you that governments and others with a technocratic/finance agenda are deceiving investors and the wider public. No matter how much we want to pin our hopes on pyrolysis of MSW, I maintain that to do so is absolute folly. People must not be deluded, and for many this seems to be a form “denial” which (though I am not a psychologist) is I believe a well understood response.

We need – MUST – look to alternatives for plastic/MSW. It is the only way, and the sooner that we start doing this the better.

I agree that the present regimes will not jump in to legislate too readily. But change is definitely coming and very soon, whether that is from a rising tide of ‘bystanders’ becoming ‘upstanders’ to peacefully oust these regime, or through catastrophic, cascade effect-driven, widespread ecological collapse.

I’m sorry that I haven’t yet directly answered your question. As a scientist/engineer, I do what I can. My response would be to say that the solution already exists: in fact it has existed for at least a decade, and ironically it is actually approved by most governments within policy! It is the waste hierarchy. This states clearly that the answer is to “reduce and reuse”. Indeed, the EU for example requires that governments implement things like repair centres! Of course, the UK at least does not, but instead funds the idea of a mysteriously novel black box technology in order to keep the throwaway society going

Thanks for your comments.

Andrew

-

52Andrew Rollinson September 2nd, 2019

Quote from Markus Gleis, 2012 (see my full journal paper):

“Belief may indeed move mountains, but modern society cannot afford to ignore the physical laws of thermodynamics and entropy. A full recovery of raw materials may be a highly anticipated wish; nevertheless it will not come true if we ignore the first or the second law of thermodynamics. This can only lead to failure and ultimately to unecessary costs”.

-

53Andrew Rollinson September 2nd, 2019

Interestingly, this new report is just out: “El Dorado of Chemical Recycling, State of play and policy challenges”: https://zerowasteeurope.eu/downloads/el-dorado-of-chemical-recycling-state-of-play-and-policy-challenges/

Some quotes:

“…the chemical recycling hype should not divert the attention from the real solution to plastic pollution which is replacing single-use plastics, detoxifying and simplifying new plastics, and designing business models to make efficient use of plastics.”

“…the best options to curb plastic pollution from environmental and economic perspective is to invest in reduction and reuse solutions; giving excessive attention to end of pipe solutions could undermine this exercise.”

“…in spite of the simplicity of this technology, pyrolysis has high energy requirements and can lead to the formation of hazardous chemicals such as Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAH) or dioxins, implying the need for further purification steps. Furthermore, it is only economically viable if the volumes are large enough, and the input stable in terms of quantity, composition and quality.

-

54Anna September 9th, 2019

Dear Dr. Rollinson,

last time I pyrolysed some waste plastic in the lab, the process used up 1.7 MJ/kg. Compare that to 32 MJ/kg which is the average heating value of waste plastic. I’m not going to read your paper because I have more important things to do, and I just can’t believe that all the inefficiencies could be so large that one could end up needing more energy than one would get from using the oil and gas.

Why don’t you contact some of the companies that are already successfully operating plastic pyrolysis plants by burning the off-gas and explain to them why what they are already doing shouldn’t be possible. I’m sure they’d have a good laugh and it would make their day. E.g. Cynar, RES Polyflow, Plastic2Oil, …

I don’t buy your arguments for why renewable energy couldn’t be used to drive the process. It just needs a large enough electricity grid that is mostly powered by renewables from which you can draw some. Maybe this doesn’t exist yet but that is where we are aiming to get!

You also conveniently neglect to mention that the pyrolytic oil can be turned back into virgin plastic again, and some of the chemicals in it can be used by the petrochemical industry for various purposes. If you use it as petrol you would have a linear system, but you don’t have to. Pyrolysis is the only way we have to almost indefinitely recycle plastic, and so it is an indispensable part of the circular economy.

Reduce and reuse is your alternative solution to the plastic problem?? Get real, man. Demand for plastics has been growing exponentially and will continue doing so for quite some time, because it’s just too useful a material. Of course we should do our best to reduce, reuse and develop alternative materials but that will in no way be enough. Too many plastic items are irreplaceable and can’t be made to be biodegradable. Just think about electronics, cars, kitchen appliances, …

Oh and I thought dioxins were only created in the presence of oxygen and at very high temperatures? Pyrolysis proceeds without oxygen by definition and at only around 450 deg C. Some plastics have oxygen in their chains but you anyway wouldn’t want to pyrolyse PET. The more common varieties like PE and PS don’t have any.

Millions of animals are dying every year from all the plastic in the oceans and you are going around trying to put people off of investing into a solution to the problem, using lots of misinformation. Honestly, you should be ashamed of yourself!

Anna

-

55Dave Darby September 9th, 2019

Anna – I’m not an expert on pyrolysis, so I’ll leave that to Andrew, but I just want to pull you up on one thing:

“Demand for plastics has been growing exponentially and will continue doing so for quite some time”

This assumes that industrial/technological society, economic growth, resource use and throughput will continue to increase, just because that’s been happening in the recent past. I think that if you look at biodiversity loss and climate change, and the fact that there’s nothing at all in place to stop them, then to assume that we can carry on the way we’ve been going is unrealistic, and in fact, attempts to do so will only hasten our demise.

-

56Mik Fielding September 10th, 2019

Dear Anna,

Well said, I was sure that the process was viable. I do agree with Andrew to the point that we need to produce far less plastic and not regard pyrolysis as an excuse to keep producing it in prodigious quantities, but it certainly has a huge part to play in recycling the vast mountains of plastics that we already have and deal with the future production which hopefully will drop enormously in the coming years.

Even then we will always have a use for the stuff and there is and will be plenty to deal with at the end of life for many plastic containing products ranging from electronics/brown goods and white goods to clothing.

Pyrolysis would appear to be one of the best, if not THE best answer to a very serious problem and I am very glad that someone with proper experience has pointed this out, thank you …

-

57Anna September 10th, 2019

Dave – I’m very concerned by the climate and biodiversity crises myself, and I do my best to avoid being given unnecessary plastic bags whenever I go shopping. I wasn’t saying that we should just go on as usual, I was just being realistic. While we in the developed world can afford the luxury of trying to reduce our plastic use and developing alternative materials, most people in developing countries have zero environmental awareness and care mainly about achieving higher living standards. So I don’t see their governments introducing many laws that could affect economic growth, at least not until things get very bad.

-

58Dave Darby September 10th, 2019

Anna – no, I agree. It’s a very tricky situation. Even if neither of us believe that we should go on as usual, in the real world, that’s exactly what every government in the world (including in the ‘overdeveloped world’) will attempt to do. And that attempt will accelerate biodiversity loss and climate change. It’s a Catch-22 situation. You’re right that this is ‘realistic’, but if this ‘realism’ continues, it will undermine our ability to survive on this planet. I think that only system change can introduce a new kind of realism – a sustainable one, but that the impetus for system change is not going to come from states or the corporate sector. It’s something that we have to build ourselves, from communities, from grassroots. If I’m honest, I’m not optimistic that this will happen in time, if at all, but in the absence of anything else, and with the current trend of authoritarians being elected with zero understanding of looming ecological collapse, I’ll keep plugging away.

-

59Andrew Rollinson September 11th, 2019

Dear Anna,

It is difficult when a blog gets to so many comments to know whether or not I should repeat myself in response to the same questions.

You are correct about the theoretical differences to the energy balance. In my journal paper I discuss this. [Incidentally, how did you obtain the enthalpy for pyrolysis? And, could you send me a link to your research results?]. Practicality however is a different matter, and I describe why a total engineering “process” plant you describe has many difficulties and energy losses that it cannot self-sustain on its own gas. Using the oil would obviously increase the chances, but [and related to your comments about dioxins], dioxins do form and concentrate in the oil. To consider the lack of input oxygen is a superficial and erroneous assumption. Look at this paper for example: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0956053X14003596 It is not open access, so, the authors say: “the toxicity rating of PCDD/F products from pyrolysis of waste was three times the input at full operational performance and eleven times the input at pilot scale”. They conclude: “Pyrolysis (of waste) cannot be safely believed to be a PCDD/F-inhibiting process” and “oil products should be used with care because they can be contaminated with PCDD/F, and the output of oil from MSW pyrolysis should either be avoided or its destination stipulated beforehand”.

In terms of the energy requirements of plastics to fuels, this recent paper in Nature is interesting: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41558-019-0459-z

It shows how plastics incineration only accounts for 9% of GHG emissions. Massive amounts come from the production process: 30% of the energy comes from converting the plastic from its resin. 60% comes from resin production.

Are you a student perhaps? Please read my paper to understand what I am and am not claiming in its findings.There is a link available somewhere higher up in the blog, it is free to access, and I hope very readable. It is in a quality journal and it was peer reviewed with excellent responses. From this, if you have any questions about my logic or methodology, please raise them here. I’d welcome that. Otherwise it is wrong and ridiculous to use phrases like “I just can’t believe”, or “oh and I thought”, and “I was sure that” (Mik). I’m not comparing my ability with Galileo, but he encountered the same deep level of denial to his carefully constructed logic, which is a natural response when there is an elephant in the room, and always occurs when someone should commit the solecism of drawing attention to it, resulting in responses which are irrational – denial, defensiveness and possibly reprisals in the form of ridicule, ostracism, and worse (1).

I agree that plastic in the biosphere is a terrible act of vandalism and barbarism.

(1) Cottey, A. 2014. Knowledge Production in a Co-operative Economy, Policy Futures in Education, 12 (4).

-

60Anna September 11th, 2019

Carefully constructed logic?? Your logic is anything but carefully constructed, unless you really are deliberately trying to confuse people: Your entire paper deals only with pyrolysis of MSW, but in this article and in these comments you pretend that your conclusions from that apply to plastic as well. Any proper scientist should know not to extend the validity of their conclusions beyond the premises they were based upon. There is a huge difference between plastic and MSW as a feedstock. True, the latter may contain a large plastic fraction but all the other materials in it reduce the overall heating value a lot (to between 6 and 10 MJ/kg, like you say in the article). It also affects the chemistry of the pyrolysis process – the oxygen and nitrogen in the biomass can combine with the hydrocarbon fragments from the plastic, meaning you will end up with less of the valuable oil and it will be of much lower quality. When you pyrolyse only plastic however (excluding PET and PVC), you end up with a large fraction of oil which is of very high quality, needing only little refining. Btw, it is the oil which is the most desirable product, not the char.

Your response regarding the dioxins is a case in point. I was talking only about plastics and then you counter that with a link to some article that talks only about MSW. The oxygen that formed the dioxins in that case probably came from the biomass, not the plastic. So you can’t use that as an argument. I’ve never heard about dioxins in plastic pyrolysis oil, you’ll need to find a reference that actually applies here to convince me.

Sorry, but you are not some lone Galileo speaking the truth to the evil capitalists. You are someone who is ideologically opposed to waste pyrolysis because you believe it will disincentivise people from reducing and reusing (a valid concern, I agree). You are just like those vegans who wrongly argue that meat is unhealthy and unnecessary because they would like it to be that way. Now I don’t know much about MSW pyrolysis (except that there is a plant in Morocco that’s doing it) and I’m not going to read your long paper on that topic because I’m only interested in plastic. So I’m not making any claims about whether MSW pyrolysis is sustainable or not. Either way, you can’t make any claims about plastic based on that.

Also your argumentation that pyrolysis can’t be self-sustaining because of the second law of thermodynamics is utter nonsense. Of course nobody is trying to build a perpetuum mobile. What people are trying to do is to find a way to make use of the energy content of the waste, which comes for free because you don’t have to pay for it, in fact you might even get paid to take it! And when it comes to plastic waste only, the energy content that you get is 32 MJ/kg, higher than that of coal. So why shouldn’t you be able to sustain your plant when you get so much energy for free?

Now like I said I am aware of the potential danger of people using more plastic if they know it can be pyrolysed, but I don’t believe this is a valid reason not to do it, because we need to do something with all the inevitable plastic waste! And the same principle applies to all kinds of technological innovations: The more efficient our machines have gotten, the cheaper our products have become and the more people have been consuming. Yes, this has led to resource overuse and is a big problem. But what are we to do about it? Go back to using old, inefficient technology so that people will use less? That’s just not going to happen. We can’t go back now, only forward. So we might as well go ahead full steam and try to build the fully circular economy with 100% renewable energy that will have to be our future if we are to survive. And plastic pyrolysis will be a fundamental part of that.

Anna

-

61Andrew Rollinson September 13th, 2019

Dear Anna,

Stick to the journal paper for the details on my research. This is a blog written in lay-terms. In my journal paper I explore waste and plastic pyrolysis as “Energy from Waste” and I have already commented with others in comment 2 about the relevance with what I discuss in my journal paper and the term “plastics to fuel”. I used the term “plastics to fuel” in the blog only because it is a non-scientific, buzz-word-type title. Maybe with hindsight that was injudicious and it has led to confusion. Again, if you have any comments on my logic of methodology in my paper, please raise them and I will respond.

I sensed that you were confused, and perhaps that you hadn’t read the earlier comments appended to this blog. Please also see my later comments about the single-feedstock plastic pyrolysis concepts where I say that time will tell whether they can be made to work (notwithstanding the energy demands of these energy intensive processing plants). For why these two terms can be grouped together, see the independent article and quotes in comment 53 which has been released after my publication.

I am not even going to begin to try and wrestle with your insults and irrational accusations.

I asked if you were a student, for I was trying to help you. The practicalities of pyrolysis may be something that you have not experienced in the lab.

You haven’t answered my question, and I am intrigued: how did you ascertain the enthalpy for pyrolysis in the lab, and can you provide a link to your experimental write-up?

Also, if you have any academic references that show a self-sustaining plastics pyrolysis plant, then please provide them.

I’d also be interested in seeing academic references that show how certain types of plastic pyrolysis do not lead to dioxins and other toxins in the oil. Such an assertion would counter the evidence provided by Chen et al. who for your information was citing plastic pyrolysis specifically and not therefore being attributable to any biomass in the feed (link provided within my comment 59 above).

May I suggest that we could end by agreeing on something? Do you or do you not agree that plastic pyrolysis is very energy intensive? Notwithstanding the fact that it perpetuates the linear economy, consider here the pre- and post- processing energy, the pyrolysis endothermicity, and the fact that ultimately the whole process is just an intermediate stage in the burning of fossil fuels? To illustrate this I provided a hyperlink (my comment 59) to the very recent paper in Nature.

Andrew

-

62Marc September 15th, 2019

Pyrolysis plants need mainly thermal energy to operate and they should be heated with waste heat from gas fired power generation plants. Typical exhaust temperatures from such plants are 500 – 800˚C. This will make the argument about the energy balance of the pyrolysis process a mute point.

-

63Paul October 16th, 2019

Andrew Rollinson. We operate a fleet of trucks that burn approx 3 million litres of fuel per annum. We are considering the installation of a 5tpd pyrolisis plant. We have access to a continuous supply of tarpaulins as the feedstock. Recognizing what you have to say about pyrolisis consuming more energy than it generates is it possible using a single clean feedstock to make this a feasible project since our objective is to produce our own diesel fuel.

Thankyou…..Paul.

-

64Mik Fielding October 17th, 2019

Paul, I would check out the makers of the 5tpd pyrolisis plant that you are considering, as they will have much more practical experience than Andrew Rollinson who bases his claims on academic research and not on many thousands of hours of actual use ‘in the field’, so to speak.

My own view as an engineer who has pioneered renewable technology for over three and a half decades, is that even if the process isn’t 100% efficient, i.e. requires an extra energy input into the system, it still has a good viable use in reclaiming plastic and potentially fuel costs. It may not reduce the latter to zero, but the overall benefit should be positive.

-

65Andrew Rollinson October 19th, 2019

Dear Paul,

I have just returned from an EfW conference in Vienna where this exact topic was presented. When I catch up with things I’ll upload a slide for you. It shows how the oil product from pyrolysis compares with the diesel specification. It doesn’t.

My advice to you is to avoid this concept.

Andrew

-

66Andrew Rollinson October 19th, 2019

Dear Paul,

I have just sent you an e-mail.

Andrew

-

67Paul October 20th, 2019

Mike Fielding. Thanks for your comments. You mention the overall benefit should be positive. My question is can this plastic to fuel process be profitable? I am going to follow up on other information sent by Andrew. I have also started a discussion with KLEAN Industries from Vancouver Canada who will present us with a quotation and design to operate the 5TPD pyrolysis plant. Once all the data from both ends of the spectrum are gathered we will make a decision to proceed or not.

Paul.

-

68Andrew Rollinson October 21st, 2019

Dear Mik,

There are two ends to the spectrum here: At one end there are indeed some academics who have never operated a gasifier or pyrolysis system, and at the other there are entrepreneurs who try to build up a company around it without the background knowledge or scientific understanding. Both are equally bad.

I wasn’t initially going to respond to your taunts, and I do not need to prove my worth to you, but my background is as follows:

I passed a PhD in thermochemical engineering, specifically building reactors and process lines for energy from waste. I did so as a mature student, having spent twenty years in a number of practical professions and working a smallholding. A few years after my PhD, I was fortunate to get a job where for three years I commissioned and operated two full-size gasifiers and essentially spent my whole time getting my hands dirty tinkering with engines and optimising the whole process line. I appeared to be the only person in the UK who was doing this, so began to get consultancy work, and since then I have worked on private-sector gasifiers and pyrolysis systems part-time as a consultant while also working part-time in academia.

Historically, and for good reason, those who have succeeded with these systems have combined practical ability with a broad scientific understanding. I am not trying to talk myself up here, but it is most relevant to the blog. People (naive investors, civil assessors, and even ‘patented blunderers’) are losing time and money by not fully understanding the complexity of this concept. Some are promoting it to be what it is not. This is folly for many reasons, one of which is our need to transition away from a wasteful and environmentally toxic system.

-

69Paul October 21st, 2019

Andrew Rollinson. Would you be able to provide me with some further information on your comment. “those who have succeeded with these systems have combined practical ability with a broad scientific understanding”. Based on our background we have the practical ability to build and mechanically operate a pyrolisis plant. We can also consult with a company (such as KLEAN Industries) or even hire a person to provide the scientific understanding. It would be helpful to have some names of those companies who have succeeded in converting plastic to oil (hopefully profitably).

Thankyou……….Paul.

-

70Andrew Rollinson October 21st, 2019

Dear Paul,

With my quote I was referring to the wake of failures with gasification and pyrolysis of mixed waste that have occurred over the last 100 years. There are lots of documents on this which I can send you if you want, but I infer from this and previous messages that you are interested in something more specifically related to your own plastic depolymerisation into diesel. It is hard for me, since I have only limited description of how you hope to run an engine on the pyrolysis products. But, I can tell you that I am hearing good things about the PLAXX RT7000 concept in the UK (which you can quickly find via an internet search). My understanding is that they are only depolymerising, and not feeding the oil to a diesel engine. This whole field is still at the concept stage. The author whom I referred you to in private e-mail might be able to assist, but I strongly suspect that even he would say that this is all too novel and that it is hard to discern facts from claims.

Good luck.

Andrew

-

71Kris October 26th, 2019

“The modern notion is to pyrolyse plastic (and other municipal refuse) into a gas or oil which is then useable as a commodity, invariably a “fuel”, in its own right. This conveniently ignores the fact that pyrolysis is an energy consuming process: more energy has to be put in to treat the waste than can actually be recovered. It can never be sustainable.”

Too many statements like that above are unsupported. Please provide citations if you are going to make such broad statements.

Take a look at this summary of a thesis on plastic pyrolysis: https://ir.canterbury.ac.nz/handle/10092/4303

In particular, it states “The actual energy consumption for cracking and vaporizing PE into fuels is 1.328 MJ/kg which is less than 3% of the calorific value of the pyrolysis products. Therefore, the pyrolysis technology has very high energy profit, 42.3 MJ/kg PE, and is environmental-friendly.”

-

72Andrew Rollinson October 29th, 2019

Dear Kris,

I believe that I have answered all of your comments previously to other respondents:

This is a blog. Please see my journal paper for the support to my claims. With that particular comment, I find that there is no evidence of a waste pyrolysis plant being capable of self-sustaining on its own products. If you know of one, please evidence it here.

I accept, and discuss in the paper, that theoretically, the LHV of the pyrolysis products can be higher than the enthalpy for pyrolysis conducted in the lab. Practically there are other engineering challenges which incur additional energy demands. In the thesis that you refer to, what are the energy demands of sorting, cleaning, shredding the plastic, how was thermodynamic stability maintained during reactor loading and unloading, what was the extent of “cracking and vaporizing” and in turn of what quality were the products? Was the oil black or was it clear, which impacts on the utility of the product, and in turn the extent of post-processing energy that will be needed to create a useful product? How was this enthalpy value determined?

I have previously also elaborated on my choice of the term “plastics to fuel” in contrast to mixed waste pyrolysis. As I have also said, time will tell whether novel pure feedstock depolymerisation technologies (aka “plastics to fuel”) can be made to work or not; but I maintain that it is not the answer to plastic waste, I strongly believe that it must incur massive energy expenditure, and I refute your (by the way – unsupported) phrase that it is “environmentally-friendly”.

-

73Tungie Asgill November 25th, 2019

Dear Anna,

We have been considering pyrolysis for some time now and are convinced that it is a viable solution; at least for the short to medium term. We are looking to run a pilot in West Africa, commencing in June 2020. However, prior to any purchasing equipment from an OEM, I was wondering if it would be possible for us to tap into your knowledge by having your opinion/feedback (positive or negative) on a specific plant that has been identified as suitable for the pilot. Or, perhaps refer us to any contacts you may have that are knowledgeable in this area.

The plant is a containerised 3ton/per day on a skid, so it is relatively small and requires no installation/commissioning. However, if the pilot is successful, we will scale up to a much larger plant. I am happy to share the plant’s specifications and all other details that have been provided by the manufacturer.

Thank you in advance for your help.

-

74Mik Fielding November 25th, 2019

Dear Anna,

I feel I have to thank you for bringing a bit of common sense to this discussion. Andrew Rollinson seems to have a one track mind as he is applying his knowledge on MSW pyrolysis to plastic on it’s own. I do think he should have made that MUCH clearer in the article and ensuing debate!

Municipal solid waste (MSW), commonly known as trash or garbage in the United States and rubbish in Britain, is a waste type consisting of everyday items that are discarded by the public. In other words, just about anything can be among this and although plastic is a large part of this these days, it is perfectly clear that the plastic involved is highly contaminated other substances.

His research basically points out that the plastics need to be seperated first, something which is worth pointing out as there are systems being sold and intalled that are being used as a do it all solution to MSW. He rightly points out the errors in this approach, but he appears to assume it is the same with a pure plastic feed and appears to argue against that as well for some reason.

I hope he hasn’t put too many people off the concept!

-

75Andrew Rollinson November 27th, 2019

I called my journal paper “Patented Blunderings” and I drew on the work of Henry Dirks in 1870, for the situation at present with these “plastic to fuels” concepts is absolutely reminiscent, and in many ways a direct extension, of the 600+ year pursuit of perpetual motion. Some quotes from Dirks are provided with the images in this blog, but here is another one which is relevant:

“…there is one point that the most enthusiastic and infatuated can never presume to have attained, and that is, to afford an ocular demonstration…” (Dircks, H. 1870).

I have previously asked on four occasions (comment 4, 59, 61, and 72) for evidence to the claims put forward by some who suggest that I am talking rot. No-one has replied.

It was to be expected that people promoting the technology with vested interests would use this blog to showcase their ideas. I mention it at the outset: it is occurring now across the world and naive investors are getting drawn in, and it occurred in Henry Dirks’ day. They perhaps have mitigating circumstances because they are seeking financial gain. But, Mik, you ignore my responses (which I have made in detail, often repeatedly throughout this blog), then when a new comment occurs (invariably by these technology providers), you repeatedly rise to the surface on its wake repeating the same unsubstantiated claims that this technology must work.

What more can I do?

To substantiate everything that I have written here, please see this very recent publication from GAIA in the US: https://www.no-burn.org/chemical-recycling/

They also corroborate why “plastic to fuel”, “chemical recycling”, “depolymerisation” are terms which cause confusion. I have not made an “error in my approach” at all. And I have not therefore “rightly pointed it out” . Your tack is becoming increasingly more dirty towards me. I said that my use of the term might have been “injudicious”, but I have repeatedly explained why I chose it, as early as comment 2, and I absolutely make no excuses for doing so. Pyrolysis IS the main technological concept use to convert plastic into fuel and the problems I describe are generic. Here is an independent appraisal from the above GAIA publication for you:

“Chemical recycling” is an industry greenwash term used to lump together various plastic-to-fuel and plastic-to-plastic technologies. These processes turn plastic into liquids or gases which could be used to make new plastic but in practice are usually burned. The terms ‘pyrolysis, ‘solvolysis’, and ‘depolymerisation’ are also used to different technological variants of this process. Whatever the process is called, if the end products are burned, its ‘plastic to fuel'”

The same resource describes the status, and why this technology IS NOT the answer to plastic waste: “the European Union has said that reploymerisation technology is at least ten years away from commercial application – far too long to tackle the climate and pollution issues posed by plastics”.

-

76Tungie Asgill November 27th, 2019

Dear Mik,

We certainly haven’t been put off the concept. In fact, we are following the lead of the Chinese. They are racing ahead with the concept; some facilitates out there are housing 10 x 10ton plants producing thousands of gallons base oil, gasoline or diesel etc.

In regards to the question that I put to Anna, can I please put forward the same question to you?

Many Thanks ?

-

77Dave Darby November 27th, 2019